Module 1: Propositional/Predicate Calculus Review #

We start with the logical connectives and truth tables which interpret the connnectives. These are really to come back to.

Logical Connectives #

(\(\neg, \land, \lor, \Rightarrow, \Leftrightarrow\))

Comment: In truth tables, I will use 0 for False, and 1 for True.

\[ \neg "NOT": \]| P | ¬P |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 |

| P | Q | (P ∧ Q) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| P | Q | (P ∨ Q) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| P | Q | (P ⇒ Q) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

NOTE: We will use \(\rightarrow\) and \(\Rightarrow\) which ARE DIFFERENT. \(\Rightarrow\) is “implies” while \(\rightarrow\) is just an arrow.

Comment: Here, note that false for P says nothing about Q. For example, the statement

"if you eat the cheeseburger, you will be full" says nothing about the scenario where you don’t eat the cheeseburger. In the cases where we can say nothing, the if statement “defaults” to true.

| P | Q | (P ⇔ Q) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

Comment: Note that every true/false pair is present. That is, we have every combination of P and Q being true/false. We have precisely \(2^n\) cases where n is the number of elements in the \( \{ \bold{P},\bold{Q} \dots \} \) set.

Tautologies & Contradictions #

A formula is said to be a tautology when its column in a truth table only consists of “trues”.

Example:

\[ P \lor (P \Rightarrow Q) \]| P | Q | (P ⇒ Q) | (P ∨ (P ⇒ Q)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Tautology

A formula is said to be a contradiction when its column in a truth table only consists of “falses”.

Example:

| \(P\) | \(Q\) | \(\neg P\) | \((P \Rightarrow Q)\) | \(\neg(P \Rightarrow Q)\) | \((\neg P \land \neg (P \Rightarrow Q))\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Contradiction

Comment: Most formulas are neither tautologies nor contradictions.

Equivalent Formulas

We say that formulas \(\phi\) and \(\psi\) are equivalent when \((\phi \Leftrightarrow \psi)\) is a tautology. This is the case exactly when the columns in the truth tables for \(\phi\) and \(\psi\) match*.

*With the caveat that the tables contain the same propositional symbols.

Example:

| \(P\) | \(\neg P\) | \(\neg \neg P\) | \((P \Leftrightarrow \neg \neg P)\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

P and \(\neg \neg P\) are equivalent.

Example:

| \(P\) | \(Q\) | \(\neg P\) | \(\neg Q\) | \((\neg P \land \neg Q)\) | \((P \lor Q)\) | \(\neg (P \lor Q)\) | \(((\neg P \land \neg Q) \Leftrightarrow \neg (P \lor Q))\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

\((\neg P \land \neg Q)\) and \(\neg (P \lor Q)\) are equivalent.

| P |

|---|

| 0 |

| 1 |

\((\neg P \Rightarrow (Q \land \neg Q))\)

| P | Q | \(\neg P\) | \(\neg Q\) | \((Q \land \neg Q)\) | \((\neg P \Rightarrow (Q \land \neg Q))\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

P and \((\neg P \Rightarrow (Q \land \neg Q))\) are equivalent.

Predicates v. Propositions A proposition is a statement/sentence that is either true or false and has no (free) variables.

Examples:

- \(\pi\) is an irrational number. (True)

- 13 is the sum of two perfect squares. (True: \(2^2 + 3^2\))

- 7587 is a prime number. (False: \(3^3 \cdot 281\))

- 14 is the best number. - Ambiguous/not well defined/not true/false (not a proposition)

- \(x^2 > 15\) — Free variable \(x\), truth value depends on \(x\), not a proposition.

- \(x^2 \geq 0\) — Free variable \(x\), not a proposition.

- For every real number \(x\), \(x^2 \geq 0\). (True: Here \(x\) is not a free variable, this is a proposition).

- There is a natural number \(x\) such that \(x^2 = 17\). (False)

Comments: In formulas, we use capital letters to represent propositions, and we can “build” more complex propositions by combining them using the logical connectives.

Using some algebra, show that \((P \Rightarrow Q)\) where

- P: “1=0”

- Q: “1=1”

Answer

Start with having 1=0.Then 0=1

Then 1+0 = 0+1

Then 1=1

Now, as it goes, we make a truth table.

| P | Q | \((P \Rightarrow Q)\) | reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | <- automatically true by “default” |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | <- automatically true by “default” |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | <- False, because we know Q is true |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | <- by our algebra |

Notice that in the third line, we used that Q is true. This might seem ambiguous right now, and that’s because it kind of is. In the future, we’ll use an equivalent statement known as the contrapositive which will verify the third line in a cleaner manner.

Also Notice we can show any two integers are equal if 0=1.

HOWEVER, we can make everything fall apart and very quickly.

Assume we know there are two numbers that aren’t equivalent.

Assume that you know that \( 17 \not= 3 \)

R: “17=3”

\( \bold{\neg R: “17\not=3”}\)

It turns out there are many ways to come to a contradiction, but one way is to show \( (P \land Q \land R) \) is a contradiction.

Note: This choice of statement is often a problem in itself. There are equivalent statements to prove the same thing.

Answer

We start by breaking the statement apart. We know that in an and (\(\land\)) statement, we need all the propositions true. Thus, we only have to check the case where we have P and Q and not R. Using our previous result, the one where you can make any two integers equal, we have that 17 = 3. As well, we have 17 is not equal to 3. A shame, truly. Also, a contradiction.A predicate is a statement with zero or more (free) variables that becomes a proposition when each (free) variable is assigned a value.

Examples: “\(\pi\) is an integer.” (Predicate with zero free variables/Proposition) (Also false)

“\(x^2 = 4\)” (Predicate with one variable: If \(x = 2\), true. If \(x = 17\), false.)

“\(x+y=7\)” (Predicate with two variables: If \(x = 1, y = 6\), true. If \(x=2, y=19\), false.)

Comments: We often use a “function-like” notation for predicates, using capital letters followed by the free variables in parentheses to represent predicates: e.g. \(P, R(x), Q(x,y),…\)

Common Sets: #

\(\emptyset = {}\) The Empty Set

\(\mathbb{N} = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, \dots}\) The Natural Numbers

\(\omega = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, \dots}\) The Whole Numbers

\(\mathbb{Z} = {\dots, -4, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, \dots}\) The Integers

\( \mathbb{Q} = \{ \frac{p}{q} \mid p \text{ and } q \text{ are integers and } q \neq 0 \} \) The Rational Numbers

\(\mathbb{P}\) The Irrational Numbers

\(\mathbb{R}\) The Real Numbers

\(\mathbb{C}\) The Complex Numbers

Comment: Only the value of a number determines what set(s) it is in, not how it is written. For example, the positive of \(\sqrt{16}\) is equal to 4, so it is in \(\mathbb{N}, \omega, \mathbb{Z}, \mathbb{Q}, \mathbb{R}\) and \(\mathbb{C}\).

Example:

\(\mathbb{Z}[i]\) “Gaussian integers” \(= \{ a + bi \mid a, b \text{ are integers} \} \)

- \(4 + 5i\) is in \(\mathbb{Z}[i]\)

- \(6 + \pi i\) is not in \( \mathbb{Z}[i] \)

- \(\frac{1}{2} - 3i\) is not in \( \mathbb{Z}[i] \)

- \(-2 + 3i\) is a Gaussian integer.

Intervals #

Intervals: Intervals are special types of sets of real numbers.

We will use the following as our definitions:

- \( (a,b) = \{x \in \mathbb{R} \mid a < x < b\} \)

- \( [a,b) = \{x \in \mathbb{R} \mid a \leq x < b\} \)

- \( (a,b] = \{x \in \mathbb{R} \mid a < x \leq b\} \)

- \( [a,b] = \{x \in \mathbb{R} \mid a \leq x \leq b\} \)

- \( (-\infty, b) = \{x \in \mathbb{R} \mid x < b\} \)

- \( (-\infty, b] = \{x \in \mathbb{R} \mid x \leq b\} \)

- \( (a, \infty) = \{x \in \mathbb{R} \mid a < x\} \)

- \( [a, \infty) = \{x \in \mathbb{R} \mid a \leq x\} \)

- \( (-\infty, \infty) = \mathbb{R} \)

Ex: \((1,5]\) has infinitely many elements, including 2,3,4,5, but also 1.036, \(\pi, \sqrt{2}, 2.7, 4.5,…\)

Also order matters:

\( [3,1) = \{x \in \mathbb{R} \mid 3 \leq x < 1 \} = \emptyset \)

vs

\( (1,3] = \{x \in \mathbb{R} \mid 1 < x \leq 3\}\) (Which is not the emptyset)

More examples:

\( [2,2] = \{x \in \mathbb{R} \mid 2 \leq x \leq 2\} = \{2\} \)

\( (2,2] = \{x \in \mathbb{R} \mid 2 < x \leq 2\} = \emptyset\)

Set Operations: #

Union: \(A \cup B = \{x \mid x \in A \lor x \in B\}\) %fix this add picture

Intersection: \(A \cap B = \{x \mid x \in A \land x \in B\}\)

Difference: \(A \setminus B = \{x \mid x \in A \land x \notin B\}\)

Comment: While the union symbol “\(\cup\)” looks like the letter, it is not the same

(\(U\) is \(\underline{\text{not}}\) the union symbol)

Truth sets of Predicates #

Let \(P(x)\) be a predicate and let \(A\) be a set. The truth set of \(P(x)\) in \(A\) is:

\( TS_A(P(x)) = \{x \in A \mid P(x) \text{ is true}\} \)

This is the set of every value in the set \(A\) that makes \(P(x)\) true.

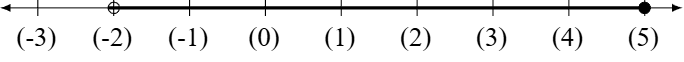

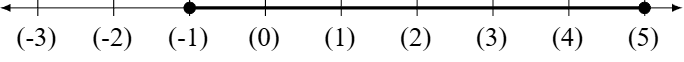

Example: Consider \(P(x)\) to be “\(-2 < x \leq 5\)”

\( TS_{\mathbb{N}}(P(x)) = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\} \)

\( TS_{\mathbb{W}}(P(x)) = \{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5\} \)

\( TS_{\mathbb{Z}}(P(x)) = \{-1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5\} \)

\( TS_{\mathbb{R}}(P(x)) = (-2, 5] \)

\( TS_{\emptyset}(P(x)) = \emptyset \)

\( TS_{\text{Primes}}(P(x)) = \{2, 3, 5\} \)

\( TS_{x^2 + 3x + 2 = 0}(P(x)) = \{ -1 \} \)

Notice that to be in \(TS_A(P(x))\), a value both needs to be in the set \(A\) and needs to make \(P(x)\) true.

Although we have different intervals that would yield the same evaluations, they are not the same. For example, when evaluating \( TS_{\mathbb{W}}(P(x))\) for \((-2,5] \text{ and } [-1,5]\), we get the same set, however, \((-2,5] \not= [-1,5]\)

An obvious observation.

Quantifiers #

A different manner in which we can convert a predicate into a proposition is by “bounding/quantifying” the free variables.

The Universal Quantifier #

The Universal Quantifier (\(\forall\))

Let \(P(x)\) be a predicate and let \(A\) be a set.

\((\forall x \in A) (P(x))\) is read “For every (all) \(x\) in \(A\), \(P(x)\).” and is true exactly when: \(TS_A (P(x)) = A\).

Example: \((\forall x \in \mathbb{N}) (x \geq 1)\) is true because: \(TS_{\mathbb{N}} (x \geq 1) = \mathbb{N}\)

\((\forall x \in \omega) (x \geq 1)\) is false because \(TS_{\omega} (x \geq 1) = {1, 2, 3, …} \neq \omega\)

Recall: The whole numbers have 0.

The Existential Quantifier #

The Existential Quantifier (\(\exists\))

Let \(P(x)\) be a predicate and let \(A\) be a set.

\((\exists x \in A) (P(x))\) is read “There exists/is an \(x\) in \(A\) such that \(P(x)\).”

and is true exactly when: \(TS_A (P(x)) \neq \emptyset\)

Example: \((\exists x \in \mathbb{N}) (x < 1)\) is false because \(TS_{\mathbb{N}} (x < 1) = \emptyset\)

\((\exists x \in \omega) (x < 1)\) is true because \(TS_{\omega} (x < 1) = {0} \neq \emptyset\)

\(TS_{\mathbb{N}}(x \geq 1) = \{1, 2, 3, \dots\} = \mathbb{N} \)

\(TS_{\omega}(x \geq 1) = \{1, 2, 3, \dots\} \neq \omega \)

\(TS_{\mathbb{N}}(x < 1) = \emptyset \)

\(TS_{\omega}(x < 1) = \{0\} \neq \emptyset\)

The Unique Existential Quantifier #

The Unique Existential Quantifier “\(\exists!\)”

Let \(P(x)\) be a predicate and let \(A\) be a set.

\((\exists!x \in A)(P(x))\) is read “There exists (is) a unique \(x\) in \(A\) such that \(P(x)\)”.

and is true exactly when \(|T S_A(P(x))| = 1\), i.e., when \(T S_A(P(x))\) has exactly one element.

Example: \((\exists!x \in \mathbb{N})(x < 1)\) is false because \(|T S_{\mathbb{N}}(x < 1)| = |\emptyset| = 0 \neq 1\)

\((\exists!x \in \omega)(x < 1)\) is true because \(|T S_\omega(x < 1)| = |{0}| = 1\)

\((\exists!x \in \mathbb{Z})(x < 1)\) is false because \(|T S_{\mathbb{Z}}(x < 1)| = |{…, -2, -1, 0 }| \neq 1\)

\((\exists!x \in \mathbb{N})(x < 4)\) is false because \(|T S_{\mathbb{N}}(x < 4)| = |{1, 2, 3 }| = 3 \neq 1\)

Comment: There are other quantifiers that can be used in addition to \(\forall\), \(\exists\), and \(\exists!\)

\(\exists!\) can be written using only \(\exists\) and \(\forall\):

\((\exists!x \in A)(P(x))\) is equivalent to:

\(\left( (\exists x \in A)(P(x)) \wedge (\forall x \in A)(\forall y \in A)((P(x) \wedge P(y)) \Rightarrow x = y)) \right)\)

An Interesting Case

For any predicate \(P(x)\), notice that: \(TS_\emptyset(P(x)) = \emptyset\).

This means that we have: \((\forall x \in \emptyset) (P(x))\) is true (no matter \(P(x)\))

and that we have: \((\exists x \in \emptyset) (P(x))\) is false (no matter \(P(x)\))

For example:

\((\forall x \in \emptyset) (x \neq x)\) is true

\((\exists x \in \emptyset) (x = x)\) is false

In any other universe/set \(A\):

\((\forall x \in A) (x \neq x)\) is false

\((\exists x \in A) (x = x)\) is true

Terminology: We say that \((\forall x \in \emptyset) (P(x))\) is vacuously true

\((\forall x \in \emptyset) (P(x)) \text{ is True}\)

\((\exists x \in \emptyset) (P(x)) \text{ is False}\)

\((\forall x \in \mathbb{Z}) (x \neq x)\)??

\(TS_{\mathbb{Z}}(x \neq x) = \emptyset \neq \mathbb{Z} \text{so False}\)

\((\exists x \in \mathbb{Z}) (x = x) \text{True}\)

\(TS_{\mathbb{Z}} (x = x) = \mathbb{Z} \neq \emptyset\)

Notation Comments:

In cases where the universe of discourse \(U\) is “understood” we may use the following notation:

\((\forall x \in U)(P(x))\) may be written: \((\forall x)(P(x))\) (Suppressing the \(U\))

\((\exists x \in U)(P(x))\) may be written: \((\exists x)(P(x))\)

As a general rule, avoid this shorthand especially when using multiple quantifiers bounding over different sets and when the universe isn’t clear.

Equivalencies: Let \(A \subseteq B\). Then, the following equivalencies hold:

\((\forall x \in A)(P(x))\) is equiv. to: \((\forall x \in B)(x \in A \Rightarrow P(x))\)

\((\exists x \in A)(P(x))\) is equiv. to: \((\exists x \in B)(x \in A \land P(x))\)

As \(A \subseteq A\) for any set:

\((\forall x \in A)(P(x))\) is equiv. to: \((\forall x \in A)(x \in A \Rightarrow P(x))\)

\((\exists x \in A)(P(x))\) is equiv. to: \((\exists x \in A)(x \in A \land P(x))\)

If we have an understood universe \(U\), and \(A \subseteq U\):

\((\forall x \in A)(P(x))\) is equiv. to: \((\forall x)(x \in A \Rightarrow P(x))\)

\((\exists x \in A)(P(x))\) is equiv. to: \((\exists x)(x \in A \land P(x))\)

Multiple Quantifiers #

Many statements will have multiple quantifiers. When this is the case, it is important to be very careful with the order.

To examine this idea:

\(P(x, y)\) is a predicate with two free variables \( x \text{ \& } y\)

\((\exists y \in B) (P(x, y))\) is a predicate with one free variable \((x)\)

\((\forall x \in A) (\exists y \in B) (P(x, y))\) is a proposition/predicate with no free variables.

Try to follow the following logic:

Please note that \(\hat{x}\) is just another variable name like x or y or whatever.

\((\forall x \in A) (\exists y \in B) (P(x, y))\) is true exactly when:

\(TS_A \left( (\exists y \in B) (P(x, y)) \right) = A\)

That is, when:

\(\left\{ x \in A \mid (\exists y \in B) (P(x, y)) \right\} = A\)

so that for every \(\hat{x} \in A\), we have that \((\exists y \in B) (P(\hat{x}, y))\) is true,

and that for every \(\hat{x} \in A\), we have that:

\(TS_B \left( P(\hat{x}, y) \right) \neq \emptyset\).

This means if we choose some \(\hat{x} \in A\), we will be able to find a value of \(y \in B\) that makes \(P(\hat{x}, y)\) true. (And the choice of \(\hat{x} \in A\) doesn’t matter)

\(TS_A (\exists y \in B)(P(x,y)) \rightarrow\) The set of all \(x \in A\) for which \((\exists y \in B)(P(x,y))\) is true.

Notice that we just said the same statement like 5 times. Also, if you didn’t follow, it might be good to take a break at this point. Come back, and try again.

An Observation: Order Matters

\((\forall x \in \mathbb{R})\ (\exists y \in \mathbb{R})\ (x+y=0) \rightarrow True\)

\(x=4 \rightarrow y=-4\)

\(x=17.2 \rightarrow y = -17.2\)

\((\exists y \in \mathbb{R})\ (\forall x \in \mathbb{R})\ (x+y=0) \rightarrow False\)

To show

\((\exists y \in \mathbb{R})\ (\forall x \in \mathbb{R})\ (x+y=0) \rightarrow False\)

- Consider \(y=7\)

\((\forall x \in \mathbb{R})\ (x+7=0)\)

This is false.

- Consider \(y=0\)

\((\forall x \in \mathbb{R})\ (x+0=0)\)

This is false.

Indeed, for any y, x + y does not HAVE TO equal 0.

Reading the statement in English. “There exists a number (y) such that any (\(\forall\)) other number (x) satisfies x + y = 0”.

Notice we just flipped the statement order. That is, order matters. \((\forall x \in \mathbb{R})\ (\exists y \in \mathbb{R})\ (x+y=0) \rightarrow True\)

\((\exists y \in \mathbb{R})\ (\forall x \in \mathbb{R})\ (x+y=0) \rightarrow False\)

More examples

\((\exists x \in \mathbb{R}) (\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) (x \leq y^2)\)

Consider \(x=1\)

\((\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) (1 \leq y^2) \rightarrow \text{False}\)

Consider \(x = -1\)

\((\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) (-1 \leq y^2) \rightarrow \text{True.}\)

This tells us that \(x = -1\) is in \(TS_{\mathbb{R}} ((\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) (x \leq y^2))\)

Thus, the truth set \(TS \neq \emptyset\)

\((\forall x \in \mathbb{R}) (\exists! y \in \mathbb{R}) (x+y=0) \rightarrow \text{True}.\)

\(\text{Next: } (\exists x \in A) (\forall y \in B) (P(x,y)) \text{ is true exactly when:}\) $$TS_A((\forall y \in B)(P(x,y))) \neq \emptyset$$ \(\text{That is, when there is at least one value of } x \in A \text{ such that }\) $$(\forall y \in B) (P(x,y)) \text{ is true.}$$ \(\text{Let } \hat{x} \in A \text{ be one of such values, i.e., so that } (\forall y \in B) (P(\hat{x},y)) \text{ is true. }\) This means that: $$TS_B (P(\hat{x},y)) = B$$ That is: $$\{y \in B \mid P(\hat{x},y) \} = B$$

\(\text{This means that for } \hat{x} \in A, \text{ we have that } P(\hat{x},y) \text{ is true for every } y \in B.\)

We will again consider:

\((\forall x \in \mathbb{R})\ (\exists y \in \mathbb{R})\ (x+y=0)\)

and

\((\exists y \in \mathbb{R})\ (\forall x \in \mathbb{R})\ (x+y=0)\)

- \((\forall x \in \mathbb{R})(\exists y \in \mathbb{R})(x+y=0)\) will be true if for every/any \(\hat{x} \in \mathbb{R}\) we can find a value \(y \in \mathbb{R}\) such that \(x+y=0\).

- This is the case: For any \(\hat{x} \in \mathbb{R}\), we can let \(y = -\hat{x}\).

Note that as \(\hat{x} \in \mathbb{R}\), \(-\hat{x}\) is also real so \(y \in \mathbb{R}\).

Also: \(\hat{x} + y = \hat{x} + (-\hat{x}) = \hat{x} - \hat{x} = 0\).

- e.g. If \(\hat{x} = 3\), we let \(y=-3\). If \(\hat{x} = -10.5\), we let \(y=10.5\).

- This is the case: For any \(\hat{x} \in \mathbb{R}\), we can let \(y = -\hat{x}\).

Note that as \(\hat{x} \in \mathbb{R}\), \(-\hat{x}\) is also real so \(y \in \mathbb{R}\).

Also: \(\hat{x} + y = \hat{x} + (-\hat{x}) = \hat{x} - \hat{x} = 0\).

- \((\exists y \in \mathbb{R})(\forall x \in \mathbb{R})(x+y=0)\) will be true if we can find some \(\hat{y} \in \mathbb{R}\) such that every \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) will make \(x + \hat{y} = 0\).

- This is not the case! No matter what \(\hat{y} \in \mathbb{R}\) we choose, there is only one value of \(x\) that will give \(x + \hat{y} = 0\) (so we will not have \(x + \hat{y} = 0\) for every real number \(x\)).

- e.g. If we tried letting \(\hat{y} = 3\), it will not be the case that \((\forall x \in \mathbb{R})(x + 3 = 0)\) will be true.

- This is not the case! No matter what \(\hat{y} \in \mathbb{R}\) we choose, there is only one value of \(x\) that will give \(x + \hat{y} = 0\) (so we will not have \(x + \hat{y} = 0\) for every real number \(x\)).

Contradiction #

| \(A\) | \(B\) | \(\neg A\) | \(\neg B\) | \((B \wedge \neg B)\) | \((\neg A \Rightarrow (B \wedge \neg B))\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Example:

A. \((\exists x \in \mathbb{R}) (\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) (x + y = y)\)

vs

B. \((\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) (\exists x \in \mathbb{R}) (x + y = y)\)

A.

- \((\exists x \in \mathbb{R}) (\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) (x + y = y) \text{ is true:}\)

- Notice that: \(TS_{\mathbb{R}}(0 + y = y) = \mathbb{R}\)

- so that: \((\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) (0 + y = y) \text{ is true.}\)

- so that: \((\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) (0 + y = y) \text{ is true.}\)

- Notice that: \(TS_{\mathbb{R}}(0 + y = y) = \mathbb{R}\)

This means that when \(x = 0\), \((\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) (x + y = y) \text{ is true.}\) \(x=0\) is in the truth set or satisfies \((\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) (x + y = y)\).

This tells us that \(TS_{\mathbb{R}}((\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) (x + y = y)) \neq \emptyset\), so that:

\((\exists x \in \mathbb{R}) (\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) (x + y = y) \text{ is } \underline{\text{true}}.\)

B.

- \((\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) (\exists x \in \mathbb{R}) (x + y = y) \text{ is also true:}\)

- No matter what value of \(\hat{y} \in \mathbb{R}\) that we choose, notice that \(0 + \hat{y} = \hat{y},\)

- so that \(0\) is in \(TS_{\mathbb{R}} (x + \hat{y} = \hat{y})\), so that \(TS_{\mathbb{R}} (x + \hat{y} = \hat{y}) \neq \emptyset\).

- No matter what value of \(\hat{y} \in \mathbb{R}\) that we choose, notice that \(0 + \hat{y} = \hat{y},\)

This gives us that \((\exists x \in \mathbb{R}) (x + \hat{y} = \hat{y}) \text{ is true.}\)

As the choice of \(\hat{y} \in \mathbb{R}\) didn’t matter, and \(\hat{y}\) is in the truth set of \((\exists x \in \mathbb{R})(x + y = y)\),

we have that \(TS_{\mathbb{R}}((\exists x \in \mathbb{R})(x + y = y)) = \mathbb{R}\), and:

\((\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) (\exists x \in \mathbb{R})(x + y = y) \text{ is } \underline{\text{true}}\).

Less formally, from left to right, for any y \((\forall y \in \mathbb{R}) \), choose x = 0 \((\exists x \in \mathbb{R})\) and the equation is true.

A Few Important Equivalencies #

\((A \Rightarrow B)\) is equiv. to: \((\neg B \Rightarrow \neg A)\) (the contraposition)

- and also: \((\neg A \vee B)\)

\(\neg (A \vee B)\) is equiv. to: \((\neg A \wedge \neg B)\) } De Morgan’s Laws

\(\neg (A \wedge B)\) is equiv. to: \((\neg A \vee \neg B)\) } De Morgan’s Laws

\(A \wedge (B \vee C)\) is equiv. to: \(((A \wedge B) \vee (A \wedge C))\) } Distribution

\(A \vee (B \wedge C)\) is equiv. to: \(((A \vee B) \wedge (A \vee C))\) } Distribution

\(\neg (A \Rightarrow B)\) is equiv. to: \((A \wedge \neg B)\)

\((\neg A \Rightarrow (B \wedge \neg B))\) is equiv. to: \(A\)

\(A \Rightarrow (B \vee C)\) is equiv. to: \((A \wedge \neg B) \Rightarrow C\)

\((A \vee B) \Rightarrow C\) is equiv. to: \((A \Rightarrow C) \wedge (B \Rightarrow C)\)

\(A \Rightarrow (B \wedge C)\) is equiv. to: \((A \Rightarrow B) \wedge (A \Rightarrow C)\)

\(A \Rightarrow (B \Rightarrow C)\) is equiv. to: \((A \wedge B) \Rightarrow C\)

\(\neg (\forall x \in A)(P(x))\) is equiv. to: \((\exists x \in A)(\neg P(x))\)

\(\neg (\exists x \in A)(P(x))\) is equiv. to: \((\forall x \in A)(\neg P(x))\)

\(\neg \neg A\) is equiv. to: \(A\) (Double negation)

A computation of a negation #

A computation of a negation

\( \neg (\forall x \in A) (P(x) \Rightarrow Q(x)) \)

\( \left(\exists x \in A\right) \left(\neg \left(P(x) \Rightarrow Q(x)\right)\right) \)

\( \left(\exists x \in A\right) \left(P(x) \wedge \neg Q(x)\right) \)

Notice we use the equivalency of: \( \neg (A \Rightarrow B) \) and \((A \wedge \neg B)\).

Breakdown

\( \neg (\forall x \in A) (P(x))\) is true exactly when \( (\forall x \in A) (P(x)) \text{ is false.} \)

\(\text{is true exactly when | } TS_A (P(x)) = \emptyset\)

\(\text{is true exactly when | there is some value } \hat{x} \in A \text{ s/t } P(x) \text{ is not true.}\)

\(\text{is true exactly when | there is some value } \hat{x} \in A \text{ s/t } P(x) \text{ is false} \)

\(\text{is true exactly when | } \text{ there is some } \hat{x} \in A \text{ s/t } \neg P(x) \text{ is true.}\)

\(\text{is true exactly when | } \text{ there is some } \hat{x} \in A \text{ is } TS_A (\neg P(x)).\)

\(\text{is true exactly when | } TS_A (\neg (P(x))) \neq \emptyset \)\

\( \text{is true exactly when | } (\exists x \in A) (\neg P(x)) \text{ is true.}\)

As well, \( \neg (\exists x \in A) (P(x)) \) and \((\forall x \in A) (\neg P(x))\) are equivalent.

Simplifying Denials/Negations. #

Goal: We want the only instances of the negation symbol “\(\neg\)” immediately preceding the predicate/propositional symbols.

Example:

\(\neg (\forall x \in A)(\forall y \in B)(\exists z \in C) ((P(x) \vee Q(y)) \Rightarrow (R(x, y, z)))\)

\((\exists x \in A)(\neg (\forall y \in B)(\exists z \in C) ((P(x) \vee Q(y)) \Rightarrow (R(x, y, z))))\)

\((\exists x \in A)(\exists y \in B)(\neg (\exists z \in C) ((P(x) \vee Q(y)) \Rightarrow (R(x, y, z))))\)

\((\exists x \in A)(\exists y \in B)(\forall z \in C)(\neg ((P(x) \vee Q(y)) \Rightarrow (R(x, y, z))))\)

\((\exists x \in A)(\exists y \in B)(\forall z \in C)((P(x) \vee Q(y)) \wedge \neg R(x, y, z))\) \

Example:

\(\neg (\exists a \in A)(\forall b \in B)(\exists c \in C)(\neg P(a) \vee (R(b) \Rightarrow S(c)))\)

\((\forall a \in A)(\exists b \in B)(\forall c \in C)(\neg(\neg P(a) \vee (R(b) \Rightarrow S(c))))\)

\((\forall a \in A)(\exists b \in B)(\forall c \in C)(\neg \neg P(a) \wedge \neg (R(b) \Rightarrow S(c)))\)

\((\forall a \in A)(\exists b \in B)(\forall c \in C)(P(a) \wedge (R(b) \wedge \neg S(c)))\)

Example: We will find/simplify a denial/negation of

\((\exists! x \in A) (P(x))\)

\(\neg (\exists! x \in A) (P(x))\) is equivalent to:

\(\neg \left( (\exists x \in A) (P(x)) \wedge (\forall y \in A) (\forall z \in A) ((P(y) \wedge P(z)) \Rightarrow y=z) \right) \) *

\(\neg (\exists x \in A) (P(x)) \vee \neg (\forall y \in A) (\forall z \in A) ((P(y) \wedge P(z)) \Rightarrow y = z) \)

\((\forall x \in A) (\neg P(x)) \vee (\exists y \in A) (\exists z \in A) \neg ((P(y) \wedge P(z)) \Rightarrow y = z) \)

\((\forall x \in A) (\neg P(x)) \vee (\exists y \in A) (\exists z \in A) ((P(y) \wedge P(z)) \wedge \neg (y = z)) \)

\((\forall x \in A) (\neg P(x)) \vee (\exists y \in A) (\exists z \in A) (P(y) \wedge P(z) \wedge y \neq z))\)

* We used this in the first step.

In english, the statement is: “Either every \( x \in A\) makes \(P(x)\) false or there are two values (or more) that make \(P\) true that are different.”

Comment:

\((A \wedge B) \wedge C\) is equiv. to \(A \wedge (B \wedge C)\) and \(A \wedge B \wedge C\)

\((A \vee B) \vee C\) is equiv. to \(A \vee (B \vee C)\) and \(A \vee B \vee C\) (Associativity) \(A \wedge B\) is equiv. to \(B \wedge A\)

\(A \vee B\) is equiv. to \(B \vee A\) (Commutativity)

Short Exercises: #

Verify that an implication \((A \Rightarrow B)\) and the converse \((B \Rightarrow A)\) are not equivalent.

| A | B | \((A \Rightarrow B)\) | \((B \Rightarrow A)\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

In this section you have to show that when you have 0 = 1, 1=1, you can’t have 17 = 3. Give another statement that if proved, would show such a thing.

Show that \((\forall x \in \mathbb{R}) (\exists! y \in \mathbb{R}) (x+y=0) \rightarrow \text{True}\) from this section.

Show the equivalency of: \( \neg (A \Rightarrow B) \) and \((A \wedge \neg B)\) from this section.