Module 3: #

Relations, Functions, Injections, Surjections, Bijections

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be two sets.

The (Cartesian) product \(A \times B\) is defined to be:

\[ A \times B = \{(a, b) \mid a \in A \land b \in B\} \]“\((a, b)\)” is the ordered pair with “a” as the first component and “\(b\)” as the second.

Notation: We may write \(A^2\) to mean \(A \times A\) (e.g., \(\mathbb{R}^2\), \(\mathbb{Z}^2\), etc.).

If \(C \subseteq A \times B\), we say that \(C\) is a relation from \(A\) to \(B\) (i.e., if \(C\) is a set of ordered pairs whose 1st components come from \(A\) and whose 2nd components come from \(B\)).

If \(C \subseteq A^2\), we say that \(C\) is a relation on \(A\).

“Idea”: A relation is a set of ordered pairs.

Let \(F \subseteq A \times B\) such that the following two properties hold:

(i). \((\forall a \in A)(\exists b \in B)((a, b) \in F)\)

(ii). \((\forall a \in A)(\forall b_1 \in B)(\forall b_2 \in B)[((a, b_1) \in F \land (a, b_2) \in F) \Rightarrow b_1 = b_2]\)

In this case, we write \(F: A \rightarrow B\) and we say “\(F\) is a function from \(A\) to \(B\)”.

If (i) doesn’t hold, but (ii) does, we write \(F : A \rightarrow B\) and say “\(F\) is a partial function from \(A\) to \(B\).”

Examples: Let \(A = \{0, 1, 2, 3, 4\}\) and let \(B = \{0, 2, 4, 6, 8\}\)

\(F_0 = \{(0, 8), (1, 6), (2, 4), (3, 2), (4, 0)\}\) \(F_0 : A \to B\)

\(F_1 = \{(0, 2), (1, 2), (2, 2), (3, 2), (4, 2)\}\) \(F_1 : A \to B\)

\(F_2 = \{(0, 0), (1, 2), (2, 4), (3, 6), (4, 8), (0, 2)\}\)

\(F_2\) is not a function from \(A\) to \(B\):

ii. fails: \((0, 0)\) & \((0, 2)\) in \(F_2\) but \(0 \neq 2\). In other words, the first component “0” goes to two different second values (0 & 2).

\(F_3 = \{(0, 2), (1, 4), (2, 6), (3, 8)\}\) \(F_3 : A \to B\)

i. fails as there is no b such that \((4,b) \in F\).

\(F_4 = \{(0, 0), (2, 1), (4, 2), (6, 3), (8, 4)\}\)

\(F_4\) is not a function from \(A\) to \(B\) as \(F \nsubseteq A \times B\)

(However: \(F_4 : B \to A\)). That is, it defines a function from \(B\) to \(A\).

If \(F : A \to B\):

- \(A = \text{dom}(F)\) “The domain of \(F\).”

- \(B = \text{cod}(F)\) “The codomain of \(F\).”

- Im\((F) = \text{ran}(F) = \{b \in B \mid (\exists a \in A) ((a, b) \in F) \}\)

“The image (or range) of \(F\).”

For \(F_0\): dom\((F_0) = A\), cod\((F_0) = B\), ran\((F_0) = B\)

For \(F_1\): dom\((F_1) = A\), cod\((F_1) = B\), ran\((F_1) = {2}\)

\[ \begin{aligned} A &= \{5, 7, 9, 11\} \\ B &= \{0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10\} \\ F &\subseteq A \times B \\ F &= \{(5,6), (9,10), (11,8), (7,6)\} \\ G &= \{(5,6), \bold{(7,10)}, (9,6), (11,10), \bold{(7,4)}\} \leftarrow \text{not a function} \end{aligned} \]

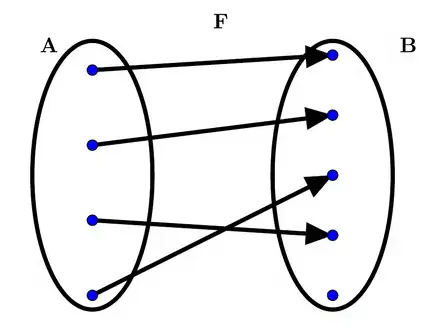

F: is a function, and

\(F: A \rightarrow B\)

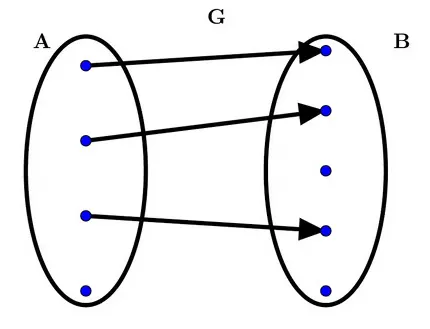

G: is a function, but not a function from \(A\) to \(B\) as (i) fails. (The “top dot” in \(A\) doesn’t correspond to a pair in \(G\).)

We do have \(G\) is a partial function from \(A\) to \(B\).

\(G: A \rightarrow B\)

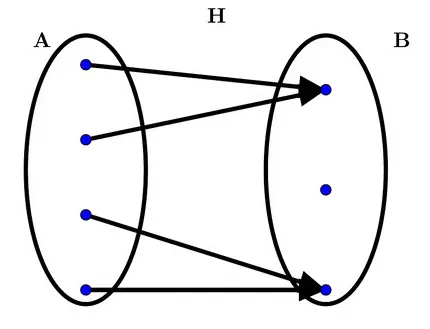

H: Is a function, and

\(H: A \rightarrow B\)

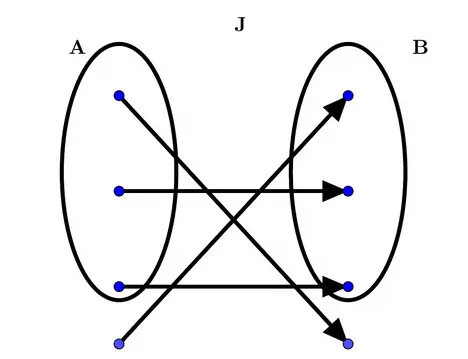

J: is not a function from \(A\) to \(B\) (as \(J \not\subseteq A \times B\)), though \(J\) is a function by using different sets \(\hat{A}\) and \(\hat{B}\) for the domain & codomain, say \(\hat{A}\) and \(\hat{B}\). Then, we could have \(J: \hat{A} \rightarrow \hat{B}\).

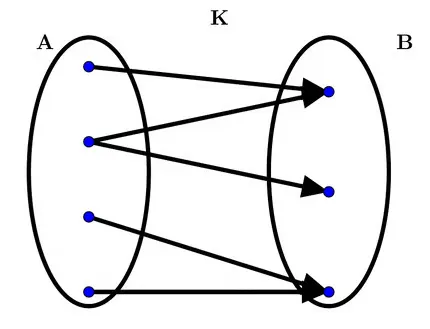

K: is not a function as (ii) fails as one point in \(A\) “goes to” different values in \(B\).

Comment: I will often refer to property (ii) as the “VLT” (the “Vertical Line Test”).

Defining Functions: When we are writing out/defining a function there are three important parts we need to identify:

- The Domain

- The Co-domain

- The Ordered Pairs in the function.

If the domain is finite, we can list out all of the ordered pairs in the function, if the domain is large or infinite, we may try to identify a rule to describe which pairs are in the function.

Notation: We may write \(f(a) = b\) to mean \((a, b) \in f\). This also gives us: \((a, f(a)) \in f\) for each \(a\) in the domain.

Example: \(f: \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\) where \(f(n) = 2n - 1\) for each \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

Example: \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) where \(f(x) = x^2\) for each \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Alternate Rule Notation “maps to”: \(a \mapsto b\) means \((a, b) \in f\), i.e., \(f(a) = b\).

Example: \(f: \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{Z}\) where \(n \mapsto (-1)^n (2n - 1)\) for each \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

\[ \begin{aligned} x+2 &= x-7 \\ 2 &\neq 0 \\ \{a,b,c\}\times\{1,2,3\} &= \{(a,1),(a,2),(a,3), (b,1), (b,2), (b,3), (c,1), (c,2), (c,3)\} \end{aligned} \]Additional Comments: Most of the functions that we will be looking at will be subsets of \(\mathbb{R}^2\). If just the “rule” is specified, we assume the domain to be as “large as possible” in \(\mathbb{R}\).

Example: Consider \(f(x) = \frac{x+2}{x-7}\). We assume that \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) (as domain & codomain were not stated).

The only value that can’t be in dom\((f)\) is 7 (can’t divide by zero). So we have:

\(f:\mathbb{R} \setminus \{7\} \to \mathbb{R}\)

One reason that we specify the codomain instead of the image/range is that it often is difficult to determine the actual range.

(In the above example, the range is actually \(\mathbb{R} \setminus \{1\}\), but this takes additional work).

Three main rules for domain:

- Can’t divide by zero \(\frac{A}{x} \implies x \neq 0\)

- Can’t take a square root (or other even root) of a negative value \(\sqrt[2n]{x} \implies x \geq 0\)

- Can’t take a log of a non-positive value \(\log(x) \implies x > 0\)

Converse Relations/Functions

Suppose that \(R \subseteq A \times B\). The converse of \(R\) is \(\hat{R} \subseteq B \times A\) and is defined by:

\[ \hat{R} = \{(b, a) \in B \times A \mid (a, b) \in R \} \]“Idea”: The converse is just the collection of all “flipped”/reversed ordered pairs.

Example: If \(R = {(0, 0), (1, 2), (2, 4), (3, 0)}\), then:

\[ \hat{R} = \{(0, 0), (2, 1), (4, 2), (0, 3)\}. \]R is a function (\(R: {0, 1, 2, 3} \rightarrow {0, 2, 4}\))

\(\hat{R}\) is not a function (VLT fails)

We will define a property to determine when the converse of a function is itself a (partial) function.

\[ \begin{aligned} &\text{L.F} (\forall a \in \mathbb{R}\setminus\{7\} \ \forall b \in \mathbb{R}\setminus\{7\} \ (F(a)=F(b) \implies a=b)) \\ &\text{Proof: Let } F: \mathbb{R}\setminus\{7\} \to \mathbb{R} \text{ be the function defined by} \\ &F(x) = \frac{x+2}{x-7} \text{ for all } x \text{ in the domain of } F. \\ &\text{Let } a \text{ and } b \text{ be arbitrary in } \mathbb{R}\setminus\{7\} \\ &\text{Assume } F(a) = F(b) \\ & \vdots (\text{show } a=b) \\ &\text{Hence, } a=b. \text{ Thus, if } F(a) = F(b), \text{ then } a=b. \\ &\text{As } a \text{ and } b \text{ were arbitrary, } F \text{ is one-to-one.} \end{aligned} \] \[ \begin{aligned} F(a)&=F(b)\\ \frac{a+2}{a-7}&=\frac{b+2}{b-7}\\ (a+2)(b-7)&=(b+2)(a-7)\\ ab-7a+2b-14&=ab-7b+2a-14\\ -7a+2b&=-7b+2a\\ -9a&=-9b\\ a&=b \end{aligned} \]In our example, the reason that \(R\) wasn’t a (partial) function was that in \(R\), two values (0 & 3) both went to 0 (so “flipping” the pairs results in 0 mapping to two different values).

This means that to ensure that the converse of \(R: A \to B\) is also a function any different values in the domain must go to different values in the codomain:

\[ (\forall a \in A) (\forall b \in A) (a \ne b \implies R(a) \ne R(b)) \]By contraposition, this is equivalent to:

\[ (\forall a \in A) (\forall b \in A) (R(a) = R(b) \implies a = b) \]Definition: Let \(F: A \to B\). We say that \(F\) is 1-1 (one-to-one) or an injection, and we write: \(F: A \overset{1-1}{\longrightarrow} B\) provided:

\[ (\forall a \in A) (\forall b \in A) (F(a) = F(b) \implies a = b) \]Outline of a proof that \(F: A \to B\) is an injection:

Proof: Set-up (Introduce / define \(F\)). Let \(a\) and \(b\) be arbitrary in \(A\). Suppose \(F(a) = F(b)\).

Now, …

Hence, \(a=b\). Thus, if \(F(a) = F(b)\), then \(a=b\). As \(a\) and \(b\) were arbitrary in \(A\) (in the domain), \(F\) is an injection (one-to-one).

Example: Let \(F: \mathbb{R} \setminus {7} \to \mathbb{R}\) be defined by \(x \mapsto \frac{x+2}{x-7}\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R} \setminus {7}\). We will prove that \(F\) is an injection.

Proof: Let \(F: \mathbb{R} \setminus {7} \to \mathbb{R}\) be the function defined by \(x \mapsto \frac{x+2}{x-7}\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R} \setminus {7}\). Let \(a\) and \(b\) be arbitrary in \(\mathbb{R} \setminus {7}\). Suppose \(F(a) = F(b)\). Now:

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{a+2}{a-7} &= \frac{b+2}{b-7} \\ (a+2)(b-7) &= (b+2)(a-7) \\ ab - 7a + 2b - 14 &= ab - 7b + 2a - 14 \\ -7a + 2b &= -7b + 2a \\ -9a &= -9b \\ a &= b. \end{aligned} \]Hence, \(a=b\). Therefore, if \(F(a) = F(b)\), then \(a=b\). As \(a\) and \(b\) were arbitrary in the domain of \(F\), \(F\) is one-to-one.

Example: Let \(g : \mathbb{Z} \to \omega\) be defined by \(n \mapsto n^2\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{Z}\). Prove that \(g\) is not one-to-one.

Logical Form: \(\neg (\forall a \in \mathbb{Z}) (\forall b \in \mathbb{Z}) (g(a) = g(b) \Rightarrow a=b)\)

We prove this using a counter example by the equivalence: \((\exists a \in \mathbb{Z}) (\exists b \in \mathbb{Z}) (g(a) = g(b) \land a \neq b)\).

Scratch Work: We need \(g(a) = g(b)\) and \(a \neq b\), i.e., we need \(a^2 = b^2\) and \(a \neq b\).

One case where this will happen is when \(a=13\) and \(b=-13\).

Proof: Let \(g : \mathbb{Z} \to \omega\) be the function defined by \(n \mapsto n^2\) for all integers \(n\). Let \(a = 13\) and let \(b = -13\). Note that both \(a\) and \(b\) are integers. Now:

\(g(a) = a^2 = 13^2 = 169 = (-13)^2 = b^2 = g(b)\).

Hence, we have that \(g(a) = g(b)\). Also, note that \(a = 13 \neq -13 = b\), so \(a \neq b\).

Thus, we have that \(g(a) = g(b)\) and \(a \neq b\). As \(a\) and \(b\) are integers, there are integers \(a\) and \(b\) such that \(g(a) = g(b)\) and \(a \neq b\). Therefore, \(g\) is not one-to-one.

Example: Let \(g: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \omega\) be defined by \(n \mapsto n^2\), for all \(n \in \mathbb{Z}\). Prove that \(g\) is not 1-1.

Logical Form: \(\neg \left( \forall a \in \mathbb{Z} \right) \left( \forall b \in \mathbb{Z} \right) \left( g(a) = g(b) \Rightarrow a=b \right)\)

We prove this using a counter example by the equivalence: \(\left( \exists a \in \mathbb{Z} \right) \left( \exists b \in \mathbb{Z} \right) \left( g(a) = g(b) \land a \neq b \right)\)

Scratch Work: We need \(g(a) = g(b)\) and \(a \neq b\), i.e., we need \(a^2 = b^2\) and \(a \neq b\). One case where this happens is when \(a = 13\) and \(b = -13\).

Proof: Let \(a = 13\) and let \(b = -13\). Note that both \(a\) and \(b\) are integers. Now:

\(g(a) = a^2 = 13^2 = 169 = (-13)^2 = b^2 = g(b)\).

Hence, we have that \(g(a) = g(b)\). Also, note that \(a = 13 \neq -13 = b\), so \(a \neq b\).

Thus, we have that \(g(a) = g(b)\) and \(a \neq b\). As \(a\) and \(b\) are integers, there are integers \(a\) and \(b\) such that \(g(a) = g(b)\) and \(a \neq b\). Therefore, \(g\) is not one-to-one.

Prove: \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}, \ x \mapsto 7-3x\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) is 1-1.

L.F. \((\forall a \in \mathbb{R})(\forall b \in \mathbb{R})(f(a) = f(b) \Rightarrow a=b)\)

Proof: Let \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) be the function defined by \(x \mapsto 7-3x\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\). Let \(a\) and \(b\) be arbitrary real numbers.

Suppose \(f(a) = f(b)\). Now:

\[ \begin{aligned} 7 - 3a &= 7 - 3b \\ -3a &= -3b \\ a &= b. \end{aligned} \]Hence, \(a = b\). Therefore, if \(f(a) = f(b)\), then \(a = b\).

As \(a\) and \(b\) were arbitrary, \(f\) is an injection.

\[ \begin{aligned} R &= \{1,2,3,4\} \times \{6,8,10\} \\ R &= \{(1,6), (1,8), (3,10)\} \text{(Not fn.)} \\ \text{Dom}(R) &= \{1,3\} \\ \text{Im}(R) &= \{6,8,10\} \end{aligned} \]We Introduced the Theorem on the next page, but have not yet gone through the proof (pg 55-56). The entire proof is scanned here so that it is complete in this file/not cut off.

\((\Rightarrow)\) Suppose that \(\hat{F}\) is a function. Let \(a\) and \(b\) be arbitrary in the domain of \(F\) and suppose \(F(a) = F(b)\). Denote the value of \(F(a) = F(b)\) by \(c\) (i.e., \(F(a) = c\) and \(F(b) = c\)). Now, we have that both \((a, c) \in F\) and \((b, c) \in F\). By the definition of the converse, we have that \((c, a) \in \hat{F}\) and \((c, b) \in \hat{F}\). As \(\hat{F}\) is a function, we have that \(a = b\). Thus, if \(F(a) = F(b)\), then \(a = b\). As \(a\) and \(b\) were arbitrary, \(F\) is one-to-one. Thus, if \(\hat{F}\) is a function, then \(F\) is one-to-one.

\((\Leftarrow)\) Now, suppose \(F\) is one-to-one. Let \(b \in B\) be arbitrary and let \(a_1\) and \(a_2\) be arbitrary in \(A\). Suppose that \((b, a_1) \in \hat{F}\) and that \((b, a_2) \in \hat{F}\). By the definition of the converse, we have \((a_1, b) \in F\) and \((a_2, b) \in F\), i.e., that \(F(a_1) = b\) and \(F(a_2) = b\). Hence, \(F(a_1) = F(a_2)\). As \(F\) is one-to-one, we have that \(a_1 = a_2\). Therefore, if \((b, a_1) \in \hat{F}\) and \((b, a_2) \in \hat{F}\), then \(a_1 = a_2\). As \(b, a_1\), and \(a_2\) were arbitrary, \(\hat{F}\) is a function. Thus, if \(F\) is one-to-one, then \(\hat{F}\) is a function.

We’ve shown both directions of the biconditional. Hence, \(\hat{F}\) is a function iff \(F\) is one-to-one.

(\(dom(\hat{F}) = ran(F)\)): Let \(x \in dom(\hat{F})\) be arbitrary. Then, there is some \(y \in A\) such that \((x,y) \in \hat{F}\). By the definition of the converse, \((y,x) \in F\). As \(y \in A\) and \((y,x) \in F\), we have that \(x \in Ran(F)\). As \(x\) was arbitrary, \(dom(\hat{F}) \subseteq Ran(F)\).

Now, let \(x \in Ran(F)\) be arbitrary. Then, there is some \(y \in A\) such that \((y,x) \in F\). By the definition of the converse, \((x,y) \in \hat{F}\). Hence, \(x \in dom(\hat{F})\). As \(x\) was arbitrary, \(Ran(F) \subseteq dom(\hat{F})\).

Thus, we have \(dom(\hat{F}) = Ran(F)\).

(\(ran(\hat{F}) = dom(F)\)): Let \(x \in ran(\hat{F})\) be arbitrary. Then, there is some \(y \in B\) such that \((y,x) \in \hat{F}\). This implies that \((x,y) \in F\). Hence, \(x \in dom(F)\). As \(x\) was arbitrary, \(ran(\hat{F}) \subseteq dom(F)\).

Now, let \(x \in dom(F)\) be arbitrary. Then, there is some \(y \in B\) such that \((x,y) \in F\). This implies that \((y,x) \in \hat{F}\). As \(y \in B\), we have that \(x \in ran(\hat{F})\). As \(x\) was arbitrary, \(dom(F) \subseteq ran(\hat{F})\).

Thus, we have \(ran(\hat{F}) = dom(F)\).

Comments/Definitions in the following proof:

i) Provided the VLT property holds for a relation, the relation will be a function for appropriate sets as the domain and codomain.

\(↪\) This means to show that \(\hat{F}\) is a function, we only need to show the VLT for \(\hat{F} \subseteq B \times A\):

\((\forall b \in B) (\forall a_1 \in A) (\forall a_2 \in A) [((b, a_1) \in \hat{F} \land (b, a_2) \in \hat{F}) \Rightarrow a_1 = a_2]\)

ii) If \(X\) and \(Y\) are sets, we say \(X = Y\) exactly when:

\((X \subseteq Y \land Y \subseteq X)\)

iii) If \(X\) and \(Y\) are sets we have \(X \subseteq Y\) exactly when:

\((\forall x)(x \in X \Rightarrow x \in Y)\)

iv) The domain of a Function/Relation \(R \subseteq A \times B\) can be defined by:

\(\text{dom}(R) = {a \in A \mid (\exists b \in B)((a,b) \in R)}\)

\[ \begin{aligned} & F: A \to B \text{ is 1-1} \\ & \text{iff} \\ & (\forall a \in A) (\forall b \in A) (F(a) = F(b) \implies a = b) \\ & G: A \to B \\ & \text{VLT:} (\forall a \in A) (\forall b_1 \in B) (\forall b_2 \in B) \left( [(a, b_1) \in G \wedge (a, b_2) \in G] \implies b_1 = b_2 \right) \\ & F: A \to B \\ & F: B \to A \end{aligned} \] \[ \begin{aligned} &F = \{(0,1), (1,1), (2, 1)\} F: \{0,1,2,3\} \rightarrow \{1\} \\ &F = \{(1,0), (1,1), (1,2)\} \end{aligned} \]Theorem: Let \(F: A \to B\), and let \(\hat{F} \subseteq B \times A\) be the converse of \(F\). Then

\[ \hat{F} \text{ is a function } \iff F \text{ is an injection}. \]Furthermore, \(\text{dom}(\hat{F}) = \text{ran}(F)\) and \(\text{ran}(\hat{F}) = \text{dom}(F)\).

Proof: Let \(F: A \to B\) and let \(\hat{F} \subseteq B \times A\) be the converse of \(F\).

(\(\implies\)) Suppose that \(\hat{F}\) is a function. Let \(a\) and \(b\) be arbitrary in the domain of \(F\) and suppose \(F(a) = F(b)\). Denote the value of \(F(a) = F(b)\) by \(c\) (i.e., \(F(a) = c\) and \(F(b) = c\)). Now, we have that both \((a,c) \in F\) and \((b,c) \in F\). By the definition of the converse, we have that \((c,a) \in \hat{F}\) and \((c,b) \in \hat{F}\). As \(\hat{F}\) is a function, we have that \(a = b\). Thus, if \(F(a) = F(b)\), then \(a = b\). As \(a\) and \(b\) were arbitrary, \(F\) is one-to-one. Thus, if \(\hat{F}\) is a function, then \(F\) is one-to-one.

(\(\impliedby\)) Now, suppose \(F\) is one-to-one. Let \(b \in B\) be arbitrary and let \(a_1\) and \(a_2\) be arbitrary in \(A\). Suppose that \((b, a_1) \in \hat{F}\) and that \((b, a_2) \in \hat{F}\). By the definition of the converse, we have \((a_1, b) \in F\) and \((a_2, b) \in F\), i.e., that \(F(a_1) = b\) and \(F(a_2) = b\). Hence, \(F(a_1) = F(a_2)\). As \(F\) is one-to-one, we have that \(a_1 = a_2\). Therefore, if \((b, a_1) \in \hat{F}\) and \((b, a_2) \in \hat{F}\), then \(a_1 = a_2\). As \(b, a_1\), and \(a_2\) were arbitrary, \(\hat{F}\) is a function. Thus, if \(F\) is one-to-one, then \(\hat{F}\) is a function.

We’ve shown both directions of the biconditional. Hence, \(\hat{F}\) is a function iff \(F\) is one-to-one.

(dom (\(\hat{F}\)) = ran(\(F\))): Let \(x \in \text{dom}(\hat{F})\) be arbitrary. Then, there is some \(y \in A\) such that \((x,y) \in \hat{F}\). By the definition of the converse, \((y,x) \in F\). As \(y \in A\) and \((y,x) \in F\), we have that \(x \in \text{Ran}(F)\). As \(x\) was arbitrary, \(\text{dom}(\hat{F}) \subseteq \text{Ran}(F)\).

Now, let \(x \in \text{Ran}(F)\) be arbitrary. Then, there is some \(y \in A\) such that \((y,x) \in F\). By the definition of the converse, \((x,y) \in \hat{F}\). Hence, \(x \in \text{dom}(\hat{F})\). As \(x\) was arbitrary, \(\text{Ran}(F) \subseteq \text{dom}(\hat{F})\).

Thus, we have \(\text{dom}(\hat{F}) = \text{Ran}(F)\).

(ran(\(\hat{F}\)) = dom(\(F\))): Let \(x \in \text{ran}(\hat{F})\) be arbitrary. Then, there is some \(y \in B\) such that \((y,x) \in \hat{F}\). This implies that \((x,y) \in F\). Hence, \(x \in \text{dom}(F)\). As \(x\) was arbitrary, \(\text{ran}(\hat{F}) \subseteq \text{dom}(F)\).

Now, let \(x \in \text{dom}(F)\) be arbitrary. Then, there is some \(y \in B\) such that \((x,y) \in F\). This implies that \((y,x) \in \hat{F}\). As \(y \in B\), we have that \(x \in \text{ran}(\hat{F})\). As \(x\) was arbitrary, \(\text{dom}(F) \subseteq \text{ran}(\hat{F})\).

Thus, we have \(\text{ran}(\hat{F}) = \text{dom}(F)\).

\[ \begin{aligned} ad - bc &= 0 \Rightarrow \\ x - y &= 0 \end{aligned} \] \[ \begin{aligned} \frac{ax + b}{cx + d} &= \frac{ay + b}{cy + d} \\ (ax + b)(cy + d) &= (ay + b)(cx + d) \\ acxy + adx + bcy + bd &= acxy + bcx + ady + bd \\ adx - bcx &= ady - bcy \\ (ad - bc)x &= (ad - bc)y \\ (ad - bc)x - (ad - bc)y &= 0 \\ (ad - bc)(x - y) &= 0 \end{aligned} \]Theorem: Let \(a, b, c,\) and \(d\) be real numbers with \(c\) and \(d\) not both equal to zero.

Let \(f : \mathbb{R} \setminus {-\frac{d}{c}} \to \mathbb{R}\) be the function defined by \(x \mapsto \frac{ax+b}{cx+d}\) for all \(x \in \text{dom}(f)\).

Then, \(f\) is \(1-1\) iff \(ad - bc \neq 0\).

For the proof of this theorem, we will use the “Zero Product Property” of the real numbers:

\[ (\forall \hat{a} \in \mathbb{R}) (\forall \hat{b} \in \mathbb{R}) (\hat{a}\hat{b} = 0 \implies (\hat{a} = 0 \vee \hat{b} = 0)) \]Logical Form: \((f \text{ is } 1-1) \iff (ad - bc \neq 0)\)

(Comment: The above form has the quantification of \(a, b, c, d\) (and \(f\)) suppressed. For \(a, b, c, d\) (and \(f\)) the universal quantifier would be used.)

Equivalent Forms:

\[ \begin{aligned} \left(\left(\forall x \in \text{dom}(f)\right) \left(\forall y \in \text{dom}(f) \right) (f(x) = f(y) \implies x = y)\right) \iff (ad - bc \neq 0) \text{(Def }1-1) \\ \left[(f \text{ is } 1-1) \implies (ad - bc \neq 0)\right] \land \left[(ad - bc \neq 0) \implies (f \text{ is } 1-1)\right] \left( \substack{\text{"Two Part"}\\ \text{proof of } \iff } \right) \\ \left[(ad - bc = 0) \implies \neg (f \text{ is } 1-1)\right] \land \left[(ad - bc \neq 0) \implies (f \text{ is } 1-1)\right] \text{(Contrapositive)} \\ \left[(ad - bc = 0) \implies \left( \exists x \in \text{dom}(f) \right) \left( \exists y \in \text{dom}(f) \right) (f(x) = f(y) \land x \neq y)\right] \\ \land \left[(ad - bc \neq 0) \implies \left( \forall x \in \text{dom}(f) \right) \left( \forall y \in \text{dom}(f) \right) (f(x) = f(y) \implies x = y)\right] \text{(Def }1-1 \text{ and negation of } 1-1) \end{aligned} \]“Full” / Quantified Logical Form:

\[ (\forall a \in \mathbb{R}) (\forall b \in \mathbb{R}) (\forall c \in \mathbb{R}) (\forall d \in \mathbb{R}) \left( \left( f(x) = \frac{ax+b}{cx+d} \right) \implies \left( \underbrace{c^2 + d^2 \neq 0}_{\substack{c \text{ \& } d \text{ not} \\ \text{both zero}}} \implies \left( \forall f \in \mathbb{R} \setminus \{-\frac{d}{c} \} , f : \mathbb{R} \setminus \{-\frac{d}{c} \} \to \mathbb{R} \right) \left( \forall x \in \mathbb{R} \setminus \{-\frac{d}{c} \} \right) (f(x) = f(y) \implies x = \hat{y}) \right) \iff (ad-bc \neq 0) \right) \] \[ \begin{aligned} &(\forall a, b, c, d \in \mathbb{R}) \Bigg[ \left( f(x) = \frac{ax + b}{cx + d} \right) \implies \Bigg( \underbrace{c^2 + d^2 \neq 0}_{\substack{c \text{ and } d \\ \text{not both zero}}} \implies \\ & \left( \forall f : \mathbb{R} \setminus \left\{ -\frac{d}{c} \right\} \to \mathbb{R},\ \forall x, y \in \mathbb{R} \setminus \left\{ -\frac{d}{c} \right\},\ f(x) = f(y) \Rightarrow x = y \right) \Bigg) \iff (ad - bc \neq 0) \Bigg] \end{aligned} \]Additional Comment: In the case where \(c=0\) (and \(d \neq 0\)), we have that \(f : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) (as \(-\frac{d}{c}\) is not defined / not a real number so that \(\mathbb{R} \setminus { -\frac{d}{c} } = \mathbb{R}\)).

The set-up of our proof will still follow this quantified form with one minor adjustment:

We won’t use the key-word “arbitrary” when introducing the function \(f\). This is due to the fact that we are defining a specific function. (We could still use the word “arbitrary” in the proof here, it just isn’t needed.)

Proof: Let a,b,c and d be arbitrary real numbers with c and d not both equal to zero. Then,

let \(f: \mathbb{R} \backslash {-d/c } \to \mathbb{R}\) be the function defined by \(x \mapsto \begin{cases} \frac{ax+b}{cx+d} \text{ for all x in the domain of f. if c≠0,}\ x+1 \text{ if c=0.} \end{cases} \)

\(\implies\) Now, suppose ad-bc = 0. let \(x = { -\frac{d}{c} +1 \text{ if c≠0,} } \)

1,C and d are real and as the reals are closed under addition, subtraction and division by non-zero values, we have that\(-\frac{d}{c} +1\) is real, so that x is real. We will show that \(x \neq -\frac{d}{c}\). Towards a contradiction, suppose \(x = -\frac{d}{c}\). Then, as \(x = -\frac{d}{c} +1\), we have that \(-\frac{d}{c} = -\frac{d}{c} +1\), so that 0=1. As O≠1, we have a contradiction.

Hence, X * -d/c. Therefore, \(X \in \mathbb{R} \backslash {-d/c }\), i.e., x is in the domain of f.

If c = 0, then we have x=1, so that x is real. When C=0,

\(\mathbb{R} \backslash {-\frac{d}{c}} = \mathbb{R} \), so that x is in the domain of f. Now, let y = x+1.

As x is real and 1 is real and the reals are closed under addition, X+l is real, so that y is real. If c≠0, we have that \(y = -\frac{d}{c}+2\). As was the case with x, we have that \(y \neq -\frac{d}{c}\), so that y is in the

domain of f. If C=0, we have that the domain of f is \(\mathbb{R} \) and y is thus in the domain. Next, we show that x≠y. If c≠0, we have \(x=-\frac{d}{c}+1\) and x = \(-\frac{d}{c}+2\). Note that \(1\neq2 \), so that \(-\frac{d}{c}+1\neq -\frac{d}{c}+2\), and x≠Y.

We now will show that we do have that \(f(x)=f(y)\). Note that:

\[ \begin{aligned} 0 &= 0 \\ 0(x-y) &= 0 \\ (ad-bc)(x-y) &= 0 \\ (ad-bc)x - (ad-bc)y &= 0 \\ (ad-bc)x &= (ad-bc)y \\ adx - bcx &= ady - bcy \\ adx + bcy &= ady + bcx \\ acxy + adx + bcy + bd &= acxy + ady + bcx + bd \\ a(cy+d) + b(cy+d) &= a(cx+d) + b(cx+d) \\ (cy+d)(ax+b) &= (cx+d)(ay+b) \\ \frac{ax+b}{cx+d} &= \frac{ay+b}{cy+d} \\ f(x) &= f(y). \end{aligned} \]Thus, we have \(f(x) = f(y)\). As \(x \neq y\) and \(f(x) = f(y)\), and \(x\) and \(y\) are in the domain of \(f\), we have that \(f\) is not one-to-one. Thus, if \(ad-bc = 0\) then \(f\) is not one-to-one. Hence, by contraposition, if \(f\) is one-to-one, then \(ad-bc \neq 0\).

\((\Leftarrow)\) Now, suppose \(ad-bc \neq 0\). Let \(x\) and \(y\) be arbitrary in the domain of \(f\).

Suppose \(f(x)=f(y)\). Now:

\(\frac{ax+b}{cx+d} = \frac{ay+b}{cy+d}\)

\((ax+b)(cy+d) = (ay+b)(cx+d)\)

\(acxy + adx +bcy +bd = acxy + ady+bcx + bd\)

\(adx +bcy - ady - bcx = 0\)

\(adx-bcx + bcy-ady = 0\)

\((ad-bc)x - (ad-bc)y = 0\)

\((ad-bc)(x-y) = 0\).

By the zero product property, we must either have that \(ad-bc=0\) or that \(x-y=0\). As \(ad-bc\neq0\), this implies that \(x-y=0\), so that \(x=y\). Thus, if \(f(x) = f(y)\), then \(x=y\). As \(x\) and \(y\) were arbitrary, for all \(x\) and \(y\) in the domain of \(f\), if \(f(x) = f(y)\), then \(x=y\). Hence, \(f\) is one-to-one. Thus, if \(ad-bc \neq 0\), then \(f\) is one-to-one.

We have shown both directions of the biconditional, hence \(f\) is 1-1 iff \(ad-bc\neq0\). As \(a, b, c,\) and \(d\) were arbitrary, for any real numbers \(a, b, c\) and \(d\) with \(c\) and \(d\) not both equal to zero, for \(f : \mathbb{R}\setminus{-\frac{d}{c}} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\), defined.

by \(x \mapsto \frac{ax+b}{cx+d}\) for every x in the domain, we have that f is an injection iff ad-bc \(\neq\) 0.

\[ \begin{aligned} & 3 \cdot 4 \mod 6 = 0 \\ & (A \implies B) \\ &= \neg B \implies \neg A \end{aligned} \] \[ \begin{aligned} f: \mathbb{R} &\to [0, \infty), x \mapsto x^2 \\ \text{Dom}(f) &= \mathbb{R} \\ \text{Cod}(f) &= [0, \infty) \\ \text{Range}(f) &= \text{Im}(f) = [0, \infty) \end{aligned} \](A \subseteq B) \ (\exists a \in A) \ (Fa = b)

Consider the function \(f : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(x \mapsto x^2\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

\[ \begin{aligned} \text{Dom}(f) &= \mathbb{R} \\ \text{Cod}(f) &= \mathbb{R} \\ \text{Im}(f) &= [0, \infty) \text{(Range)} \end{aligned} \]Visually, this is because \(f\) fails the “Horizontal Line Test” (HLT).

If we “changed” the codomain and considered \(\hat{f} : \mathbb{R} \to [0, \infty)\) defined by \(x \mapsto x^2\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\), then we would have that the codomain and the image/range would be equal / the same.

If a function is such that the codomain and image are equal (the same), i.e., if \(\text{Cod}(f) = \text{Im}(f)\), we say that the function is onto or is a surjection.

In this case, we may write: \(f : A \xrightarrow{\text{onto}} B\).

Surjections / Onto Functions #

A function \(f: A \to B\) is onto / a surjection when \(\text{Cod}(f) = \text{Im}(f)\).

This “means” that everything in \(B\) needs to be mapped to by at least one value in \(A\) (the domain).

\(f: A \to B\) is not onto, not 1-1.

\(g: A \to B\) is not onto, is 1-1.

\(h: A \to B\) is is onto, not 1-1.

\(k: A \to B\) is is onto, is 1-1.

Notice that being 1-1 & onto are unrelated (one doesn’t imply / give the other).

\[ \begin{aligned} F: A \rightarrow B \text{ is 1-1 iff } (\forall a \in A) (\forall b \in A) (f(a) = f(b) \Rightarrow a = b) \text{ (Injection)} \\ F: A \rightarrow B \text{ is onto iff } (\forall b \in B) (\exists a \in A) (f(a) = b) \text{ (Surjection)} \\ \text{iff} \text{Cod}(f) = \text{Range}(F) \end{aligned} \]Onto: \((\forall b \in B)(\exists a \in A)(f(a) = b)\)

want \(f(a) = b\)

\(a - 7 = b\)

\(a = b + 7\)

The Logical Form of the Definition of Onto \ A function \(f: A \rightarrow B\) is onto/a surjection iff:

\[ (\forall b \in B)(\exists a \in A)(f(a) = b) \]“For every value \(b\) in \(Cod(f) = B\), we can find a value \(a\) in \(Dom(f) = A\), such that \(f\) maps/takes \(a\) to \(b\).”

``Outline’’ of a proof that \(F: A \rightarrow B\) is a surjection:

Proof: (Introduce the function) \ Let \(b\) be arbitrary in \(B\). \ Let \(a = \text{(value found in scratch work)}\). \ (Show \(a \in A\))*

- In many cases this is done by contradiction & closure properties.

Now: \(f(a) = \dots = b\). (``calculation’’) \ Thus, \(f(a) = b\). As \(a \in A\), there exists an \(a\) in \(A\) such that \(f(a) = b\). \ As \(b\) was arbitrary, for all \(b\) in \(B\), there is an \(a\) in \(A\) such that \(f(a) = b\). Thus, \(f\) is a surjection/is onto.

Example: We will prove that \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\), defined by \(f(x) = 2x - 7\) is onto.

Logical Form: \((\forall b \in \mathbb{R}) (\exists a \in \mathbb{R}) (f(a) = b)\)

Scratch Work: We need \(f(a) = b: 2a - 7 = b \implies 2a = b + 7 \implies a = \frac{b+7}{2}\).

Proof: Let \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) be the function defined by \(x \mapsto 2x - 7\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Let \(b\) be an arbitrary real number. Let \(a = \frac{b+7}{2}\). Notice that \(2\), \(7\), and \(b\) are real numbers, so that as the reals are closed under addition and division by non-zero values, \(\frac{b+7}{2}\) is real. Hence, we have that \(a\) is real, i.e., that \(a\) is in the domain of \(f\).

Now:

\[ f(a) = 2a - 7 = 2\left(\frac{b+7}{2}\right) - 7 = (b+7) - 7 = b. \]Hence, we have that \(f(a) = b\). As \(a\) is real, there is a real number \(a\) such that \(f(a) = b\). As \(b\) was arbitrary, for all real numbers \(b\), there exists a real number \(a\) such that \(f(a) = b\). Hence, \(f\) is a surjection.

Example: We will prove that \(f: \mathbb{R} \setminus {7} \to \mathbb{R} \setminus {5}\) defined by \(x \mapsto \frac{5x-2}{x-7}\) is onto.

Logical Form: \(\left(\forall b \in \mathbb{R} \setminus {5}\right) \left( \exists a \in \mathbb{R} \setminus {7} \right) \left( f(a) = b \right)\)

Scratch Work: Need to find \(a \in \mathbb{R} \setminus {7}\) such that \(f(a) = b\): \(\frac{5a-2}{a-7} = b\)

\(\Rightarrow (5a-2) = b(a-7) \Rightarrow 5a-2 = ab - 7b \Rightarrow 5a - ab = 2 - 7b\)

\(\Rightarrow a(5-b) = 2-7b \Rightarrow a = \frac{2-7b}{5-b}\).

Closure properties of \(\mathbb{R}\) (and that \(b \neq 5\)) will give us \(a \in \mathbb{R}\).

We will use a contradiction to show \(a \neq 7\). (Assume \(a = 7\) and get a false statement).

Proof: Let \(f: \mathbb{R} \setminus {7} \to \mathbb{R} \setminus {5}\) be the function defined by \(f(x) = \frac{5x-2}{x-7}\) for all \(x\) in \(\mathbb{R} \setminus {7}\). Let \(b\) be in \(\mathbb{R} \setminus {5}\) be arbitrary. Let \(a = \frac{2-7b}{5-b}\). Note that \(b \neq 5\), so that \(5-b \neq 0\). As, 2, 5, 7 and \(b\) are real, and as \(5-b \neq 0\), we have that as the reals are closed under subtraction, multiplication and division by non-zero values, \(\frac{2-7b}{5-b}\) is real, i.e., \(a\) is real.

We claim that \(a \neq 7\). Towards a contradiction, suppose \(a=7\). Now:

\[ a = \frac{2-7b}{5-b} \] \[ 7 = \frac{2-7b}{5-b} \] \[ \begin{aligned} 7(5-b) &= 2 - 7b \\ 35 - 7b &= 2 - 7b \\ 35 &= 2. \end{aligned} \]Now, we have that \(35 = 2\). As \(35 \neq 2\), we have a contradiction, hence \(a \neq 7\), as claimed. Thus, \(a \in \mathbb{R} \setminus {7}\), that is a is in the domain of \(f\).

Now, notice:

\[ \begin{aligned} f(a) &= \frac{5a - 2}{a - 7} \\ &= \frac{5(\frac{2-7b}{5-b}) - 2}{(\frac{2-7b}{5-b}) - 7} \\ &= \frac{5(2-7b) - 2(5-b)}{(2-7b) - 7(5-b)} \\ &= \frac{10 - 35b - 10 + 2b}{2 - 7b - 35 + 7b} \\ &= \frac{-33b}{-33} \\ &= b. \end{aligned} \]Hence, \(f(a) = b\). As \(a \in Dom(f)\), then is an \(a \in Dom(f)\) such that \(f(a) = b\). As \(b \in Cod(f)\) was arbitrary, for all \(b \in Cod(f)\), there is an \(a \in Dom(f)\) such that \(f(a) = b\). Hence, \(f\) is onto.

Example: We will prove that \(f: \mathbb{R}\setminus{\frac{9}{8}} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(x \mapsto \frac{2x+1}{8x-9}\) is not a surjection.

Logical Form: \(\neg (\forall b \in \mathbb{R})(\exists a \in \mathbb{R}\setminus {\frac{9}{8}}) (f(a)=b)\)

Equivalent Form (simplified): \((\exists b \in \mathbb{R}) (\forall a \in \mathbb{R}\setminus{\frac{9}{8}}) (f(a) \neq b)\)

We need to find a real number \(b\) that nothing in the domain maps to.

We will examine \(f(a) = \frac{2a+1}{8a-9}\)

\[ \begin{array}{r} \frac{1}{4} \\ 8a-9 \overline{) 2a+1} \\ \underline{-(2a - \frac{9}{4})} \\ \frac{13}{4} \end{array} \]Now: \(f(a) = \frac{2a+1}{8a-9} = \frac{1}{4} + \frac{\frac{13}{4}}{8a-9}\)

This means that \(f(a)\) can’t equal \(\frac{1}{4}\) (this is the value of \(b\) we were looking for)

(Never equals zero (\(\frac{A}{B} = 0\) iff \(A=0\) & \(B\neq0\)))

Comment: We could also look at the graph, which has a horizontal asymptote at \(y = \frac{1}{4}\), which the curve doesn’t cross.

Proof: Let \(f: \mathbb{R} \setminus {\frac{9}{8}} \to \mathbb{R}\) be the function defined by \(f(x) = \frac{2x+1}{8x-9}\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R} \setminus {\frac{9}{8}}\). Let \(b = \frac{1}{4}\). Note that \(b \in \mathbb{R}\), so that \(b\) is in the codomain of \(f\). Now, let \(a \in \mathbb{R} \setminus {\frac{9}{8}}\) be arbitrary. We will show that \(f(a) \ne b\). Towards a contradiction, suppose \(f(a) = b\). Now:

\[ \frac{2a+1}{8a-9} = \frac{1}{4} \] \[ 4(2a+1) = 8a-9 \] \[ 8a + 4 = 8a - 9 \] \[ 4 = -9 \]Now, we have \(4 = -9\). As \(4 \ne -9\), we have a contradiction. Hence, \(f(a) \ne b\). As \(a\) was arbitrary, for every \(a\) in the domain, \(f(a) \ne b\). As \(b\) is in the codomain, there is a \(b\) in the codomain, such that for all \(a\) in the domain, \(f(a) \ne b\). Hence, \(f\) is not a surjection.

Bijections #

\[ \begin{aligned} 1 &\mapsto (1,1) \mapsto 1 \\ 2 &\mapsto (1,2) \mapsto \frac{1}{2} \\ 3 &\mapsto (2,1) \mapsto 2 \\ 4 &\mapsto (3,1) \mapsto 3 \\ 5 &\mapsto (2,2) \mapsto 1 \\ 6 &\mapsto (1,3) \mapsto \frac{1}{3} \\ 7 &\mapsto (1,4) \mapsto \frac{1}{4} \\ 8 &\mapsto (2,3) \mapsto \frac{2}{3} \\ 9 &\mapsto (3,2) \mapsto \frac{3}{2} \\ 10 &\mapsto (4,1) \mapsto 4 \\ 11 &\mapsto (5,1) \mapsto 5 \\ 12 &\mapsto (4,2) \mapsto 2 \\ 13 &\mapsto (3,3) \mapsto 1 \\ 14 &\mapsto (2,4) \mapsto \frac{1}{2} \\ 15 &\mapsto (1,5) \mapsto \frac{1}{5} \\ 16 &\mapsto (1,6) \mapsto \frac{1}{6} \\ & (1234, 7215) \frac{1234}{7215} \end{aligned} \]As we noted earlier, functions can be either 1-1 or onto or both or neither. If \(f: A \to B\) is both 1-1 and onto, we write \(f: A \overset{1-1}{\underset{onto}{\to}} B\) and we say that \(f\) is a bijection (or a one-to-one correspondence).

To prove that \(f: A \to B\) is a bijection, we prove both that it is 1-1 and is onto and then conclude that \(f\) is a bijection.

Example: We will prove \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\), defined by \(x \mapsto x-7\) is a bijection.

Proof: Let \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) be the function defined by \(f(x) = x-7\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

(1-1): Let \(a\) and \(b\) be arbitrary in the domain, and suppose that \(f(a) = f(b)\). Now:

\[ \begin{aligned} a-7 &= b-7 \\ a &= b. \end{aligned} \]Hence, \(a=b\). Thus, if \(f(a) = f(b)\), then \(a = b\). As \(a\) and \(b\) were arbitrary, for all \(a\) and \(b\) in the domain, if \(f(a) = f(b)\), then \(a = b\). Thus, \(f\) is an injection.

(Onto): Let \(b\) be arbitrary in the codomain. Let \(a = b+7\). As \(b\) is in the codomain, \(b\) is real. As \(7\) and \(b\) are real, and as the reals are closed under addition, \(b+7\) is real, i.e., \(a\) is real and is in the domain of \(f\). Now:

\[ \begin{aligned} f(a) = a - 7 = (b+7) - 7 = b. \end{aligned} \]Thus, \(f(a) = b\). As \(a\) is in the domain, there is an \(a\) in the domain such that \(f(a) = b\). As \(b\) was arbitrary, for all \(b\) in the codomain, there is an \(a\) in the domain such that \(f(a) = b\). Hence, \(f\) is a surjection.

As \(f\) is both an injection and a surjection, \(f\) is a bijection.

We will now “construct” a surjection \(f: \mathbb{N} \to (0, \infty) \cap \mathbb{Q}\).

- This “weaving” pattern will hit every ordered pair of positive integers;

- This means that we will get every fraction of positive integers.

- As every positive rational number can be written as \(\frac{a}{b}\) for \(a,b\) positive integers, \(f\) will be onto \((0,\infty) \cap \mathbb{Q}\).

We “associate” an ordered pair \((a,b)\) with the rational number equal to \(\frac{a}{b}\).

We “map” each natural number to the rational number associated with the corresponding dot/point.

\[ \begin{aligned} 1 & \mapsto 1 ((1,1) \mapsto \frac{1}{1}) \\ 2 & \mapsto \frac{1}{2} ((1,2) \mapsto \frac{1}{2}) \\ 3 & \mapsto 2 ((2,1) \mapsto \frac{2}{1}) \\ 4 & \mapsto 3 ((3,1) \mapsto \frac{3}{1}) \\ 5 & \mapsto 1 ((2,2) \mapsto \frac{2}{2}) \\ 6 & \mapsto \frac{1}{3} ((1,3) \mapsto \frac{1}{3}) \\ 7 & \mapsto \frac{1}{4} ((1,4) \mapsto \frac{1}{4}) \\ 8 & \mapsto \frac{2}{3} ((2,3) \mapsto \frac{2}{3}) \\ 9 & \mapsto \frac{3}{2} ((3,2) \mapsto \frac{3}{2}) \\ 10 & \mapsto 4 ((4,1) \mapsto \frac{4}{1}) \\ & \vdots \end{aligned} \] \[ \begin{aligned} & A \\ & f: A \rightarrow B \\ & B \\ & |A|=6 \\ & |B|=6 \end{aligned} \]The sets A and B have the following elements:

\(A = {0,1,2,3,4,5}\) \(B = {2,6,8,10,12,16}\)

The function f maps as follows: \(f(0) = 2\) \(f(1) = 6\) \(f(2) = 8\) \(f(3) = 10\) \(f(4) = 12\) \(f(5) = 16\)

The function \(f : \mathbb{N} \to (0,\infty) \cap \mathbb{Q}\) that we just described is not an injection (not 1-1).

In fact, every positive rational number will be mapped to by infinitely many values from the domain.

We already have that \(f(1) = f(5)\) (both equal 1) with \(1 \neq 5\). (We also will have \(f(13) = 1\)).

Any time the “path” hits \((n,n)\), the output will be 1.

While \(f\) is not 1-1, we can use it to “build” a bijection between \(\mathbb{N}\) and \((0,\infty) \cap \mathbb{Q}\).

The “idea” will be to “skip over” values we already have mapped to.

\[ \begin{aligned} f(1) &= 1 = g(1) \\ f(2) &= \frac{1}{2} = g(2) \\ f(3) &= 2 = g(3) \\ f(4) &= 3 = g(4) \\ f(5) &= 1 \text{(skip)} \\ f(6) &= \frac{1}{3} = g(5) \\ f(7) &= \frac{1}{4} = g(6) \\ f(8) &= \frac{2}{3} = g(7) \\ f(9) &= \frac{3}{2} = g(8) \\ f(10) &= 4 = g(9) \\ f(11) &= 5 = g(10) \end{aligned} \] \[ \begin{aligned} f(12) &= 2 \text{(skip)} \\ f(13) &= 1 \text{(skip)} \\ f(14) &= \frac{1}{2} \text{(skip)} \\ f(15) &= \frac{1}{5} = g(11) \\ f(16) &= \frac{1}{6} = g(12) \\ f(17) &= \frac{2}{5} = g(13) \\ f(18) &= \frac{3}{4} = g(14) \\ f(19) &= \frac{4}{3} = g(15) \\ f(20) &= \frac{5}{2} = g(16) \\ &\vdots \end{aligned} \]We will have \(g: \mathbb{N} \xrightarrow[\text{onto}]{1-1} (0, \infty) \cap \mathbb{Q}\)

- As \(f\) was onto, \(g\) still will be.

- As we skip “duplicate” values, \(g\) will be 1-1.

Cardinality of Sets

Two sets \(A\) and \(B\) are said to have the same cardinality if there is a bijection \(f : A \xrightarrow[onto]{1-1} B\).

In this case, we write: \(|A| = |B|\)

If a set is finite, then we write \(|A| = n\) where \(n\) is the number of elements in \(A\).

If \(|A| = |\mathbb{N}|\), i.e., if there is a bijection \(f : \mathbb{N} \xrightarrow[onto]{1-1} A\), we say that \(A\) is denumerable, and we write \(|A| = \aleph_0\).

Example: Our last function \(g : \mathbb{N} \xrightarrow[onto]{1-1} (0, \infty) \cap \mathbb{Q}\), so we have that:

\(|(0, \infty) \cap \mathbb{Q}| = \aleph_0\)

Example: Consider \(f : \mathbb{N} \xrightarrow[onto]{1-1} \omega\) defined by \(n \mapsto n-1\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). As this is a bijection, we have \(|\omega| = \aleph_0\)

Example: Consider \(h : \mathbb{N} \xrightarrow[onto]{1-1} \mathbb{N}\) defined by \(n \mapsto n\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). (h is the identity function on \(\mathbb{N}\)). Thus, we have \(|\mathbb{N}| = \aleph_0\).

\[ \begin{aligned} & |A| = |B| \text{iff} \exists f: A \xrightarrow{\text{1-1}} B \\ & |A| = \aleph_0 \text{iff} \text{``A is denumerable''} \text{iff} |A| = |\mathbb{N}| \\ & \text{If A has n-many elements (for some } n \in \mathbb{N}), \text{ A is ``finite''} \\ & |\emptyset| = 0 |\{2, 7, 13, 5, -83\}| = 5 \\ & \left( \text{If A is finite or denumerable, A is countable} \right) \end{aligned} \] \[ \begin{aligned} & |\mathbb{N}| = |\mathbb{Z}| \\ & \text{Find } f: \mathbb{N} \xrightarrow{\text{1-1}} \mathbb{Z} \\ & \text{onto} \\ & \begin{array}{ccc} 1 & \mapsto & 0 \\ 2 & \mapsto & 1 \\ 3 & \mapsto & 2 \\ 4 & \mapsto & -1 \\ 5 & \mapsto & 3 \\ 6 & \mapsto & -2 \\ \vdots \end{array} \end{aligned} \] \[ \begin{aligned} & n \mapsto \begin{cases} -\frac{n-1}{2} & \text{if \\(n\\) is odd} \\ \frac{n}{2} & \text{if \\(n\\) is even} \end{cases} \\\\ \text{Goal:} & f : \mathbb{N} \xrightarrow{\text{onto}} \mathbb{Z} \end{aligned} \] \[ \begin{aligned} 1 & \mapsto 1 2(0) +1 \mapsto 0 n = 2k+1 \\ 2 & \mapsto -1 2(1) +1 \mapsto 1 k= \frac{n-1}{2} \\ 3 & \mapsto 2 \\ 4 & \mapsto -2 \\ 5 & \mapsto 3 \\ 6 & \mapsto -3 \\ 7 & \mapsto 4 \\ 8 & \mapsto -4 \\ 9 & \mapsto -7 \end{aligned} \]A = {1,2,3,4,5} |A| = 5

A \text{ is countable so there should be}

f: \mathbb{N} \xrightarrow{\text{onto}} A

1 \mapsto 1 2 \mapsto 2 3 \mapsto 3 4 \mapsto 4 5 \mapsto 5 6 \mapsto 1 7 \mapsto 2 8 \mapsto 3 9 \mapsto 4

Example: Consider \(j : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{Z}\) defined by

\[ j(n) = \begin{cases} \frac{n-1}{2} & \text{if } n \text{ is odd,} \\ -\frac{n}{2} & \text{if } n \text{ is even.} \end{cases} \text{ For all } n \in \mathbb{N}. \]This gives us that \(|\mathbb{Z}| = \aleph_0\).

\[ \begin{aligned} 1 &\mapsto 0 \\ 2 &\mapsto -1 \\ 3 &\mapsto 1 \\ 4 &\mapsto -2 \\ 5 &\mapsto 2 \\ 6 &\mapsto -3 \\ 7 &\mapsto 3 \\ 8 &\mapsto -4 \\ &\vdots \end{aligned} \]A set \(A\) is said to be countable if either \(A\) is finite or if \(A\) is denumerable.

In other words, \(A\) is countable if either \(|A| = \aleph_0\) or if there is some \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \(|A| = n\).

Fact: A set \(A\) is countable exactly when there is a surjection from \(\mathbb{N}\) to \(A\), i.e., there is some \(f : \mathbb{N} \twoheadrightarrow A\).

We will show that the interval (0,1) (of real numbers) is not countable.

To do this, we will show that every function \(f:\mathbb{N} \rightarrow (0,1)\) is not onto.

This means that there will always be a value in (0,1) that is not in the image/range of the function.

Fact we will use: Every real number in (0,1) can be written in the form:

\(y = \sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac{y_n}{10^n}\) where each \(y_n \in {0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9}\)

(This is the listing of all the digits in y in the decimal expansion)

For example: If \(y=\frac{1}{13}\), we have \(y=0.0769230769230…\)

Here: \(y_1=0\), \(y_2=7\), \(y_3=6\), \(y_4=9\), \(y_5=2\), \(y_6=3\), \(y_7=0\), …

Comment: The decimal expansion may not actually be unique. This won’t matter for us right now, but it’s important to be aware (In the actual proof, it will come up)

Example: If \(y=\frac{23}{100}\) we have both: \(y = 0.23000000…\) and \(y = 0.22999999…\)

The expansions can be made unique by not allowing the “tailing” 9’s.

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{1}{2}&=0.500000... \\ y_1&=5\\ y_2&=0\\ y_3&=0\\ y_4&=0\\ 0.99999... &= 1 \\ \frac{1}{2} &= 0.499999... \end{aligned} \]Let \(f: \mathbb{N} \to (0,1)\) be an arbitrary function. We will show \(f\) is not onto by finding a value \(b \in (0,1)\) which is not in the range/image of \(f\).

Logical Forms: \(\neg\) (\(f\) is onto)

\( \neg (\forall b \in (0,1)) (\exists a \in \mathbb{N}) (f(a)=b)\)

\( (\exists b \in (0,1)) (\forall a \in \mathbb{N}) (f(a) \neq b)\)

We don’t know what \(f\) maps values to precisely, however, we can write the following:

\(f(1) = y_1 = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{y_{1n}}{10^n} = 0.y_{11} y_{12} y_{13} y_{14} y_{15} y_{16} \dots\)

\(f(2) = y_2 = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{y_{2n}}{10^n} = 0.y_{21} y_{22} y_{23} y_{24} y_{25} y_{26} \dots\)

\(f(3) = y_3 = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{y_{3n}}{10^n} = 0.y_{31} y_{32} y_{33} y_{34} y_{35} y_{36} \dots\)

\(\vdots\)

\(f(m) = y_m = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{y_{mn}}{10^n} = 0.y_{m1} y_{m2} y_{m3} y_{m4} y_{m5} y_{m6} \dots\)

Comment: Notationally it would be better to put a comma ‘,’ between the subscripts (and necessary for larger values).

We now will define/create a number \(b\) as follows:

\[ b = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{b_n}{10^n} = 0.b_1b_2b_3b_4b_5b_6... \]Where:

\[ b_n = \begin{cases} 3 & \text{if } y_{nn} \ne 3, \\ 7 & \text{if } y_{nn} = 3. \end{cases} \]Idea: We look at the \(n^{th}\) digit of \(f(n)\) and change it to something different.

Example: Suppose \(f\) gave us the following:

\(f(1) = 0.6 \circled{9} 54405…\) \(f(2) = 0.4 \circled{0} 86829…\) \(f(3) = 0.69 \circled{6} 1720…\) \(f(4) = 0.998 \circled{5} 129…\) \(f(5) = 0.986 \circled{0} 307…\) \(f(6) = 0.78896 \circled{3} 6…\) \(f(7) = 0.395945 \circled{6}…\)

The \(n^{th}\) digit of \(f(n)\) is circled.

This allows us to begin to write \(b = 0.3333773…\)

Notice that \(b\) only has 3’s & 7’s, so it can’t have trailing 9’s, nor will it terminate (i.e., trailing 0’s).

\[ \begin{aligned} y_{17,56} &\rightarrow 56^{\text{th}} \text{ digit of } f(17)\\ y_{1,756} &\rightarrow 756^{\text{th}} \text{ digit of } f(1) \\ y_{175,6} &\rightarrow 6^{\text{th}} \text{ digit of } f(175) \end{aligned} \]As \(b\) will not have trailing 9’s nor 0’s, the representation is unique, i.e., there is no other decimal expansion for the same value.

This means that if \(b=a\), every digit in the decimal expansions must match/be the same.

(i.e., \(b_1=a_1, b_2=a_2, b_3=a_3, b_4=a_4\), etc…)

Now:

- \(b \neq f(1)\) as \(b_1 \neq y_{11}\) (the first digits are different)

- \(b \neq f(2)\) as \(b_2 \neq y_{22}\) (the second digits are different)

- \(b \neq f(3)\) as \(b_3 \neq y_{33}\) (the third digits are different)

- \(\vdots\)

- \(b \neq f(m)\) as \(b_m \neq y_{mm}\) (the \(m^{th}\) digits are different)

- \(\vdots\)

This tells us that no matter what \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) we plug in, we will not get \(b\).

In other words, \(b\) is not in the range (but \(b\) is in \((0,1)\), the codomain).

Thus, \(f\) is not onto. (\(Cod(f) \neq Range(f)\))

As \(f\) was arbitrary, any function \(f: \mathbb{N} \to (0,1)\) will not be a surjection.

Comment: The “b” will be different for each \(f: \mathbb{N} \to (0,1)\), but we find such a “b” using the same process.

We’ve just seen that any function \(f: \mathbb{N} \to (0,1)\) cannot be onto, so that any function \(f: \mathbb{N} \to (0,1)\) cannot be a bijection.

This means that \(|\mathbb{N}| \neq |(0,1)|\) (Different Cardinalities), so that \(|(0,1)| \neq \aleph_0\).

We also know that \((0,1)\) is not finite, so that \((0,1)\) is not countable.

Aside: While \(f: \mathbb{N} \to (0,1)\) cannot be onto, it is possible for \(f\) to be 1-1.

For example, consider:

\(f: \mathbb{N} \to (0,1)\) defined by \(n \mapsto \frac{1}{n+1}\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

The same type of process also gives us that any function \(f: \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{R}\) cannot be onto (just make \(b \in \mathbb{R}\) such that \(b\) “disagrees” with the \(n^{\text{th}}\) digit of \(f(n)\).)

This means that \(|\mathbb{N}| \neq |\mathbb{R}|\) and \(|\mathbb{R}| \neq \aleph_0\).

\((0,1)\) vs \(\mathbb{R}\)

\(f : (0,1) \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\)

\(f_2\) – not 1-1, not onto

\(f_c\) – not 1-1, is onto

\[ \begin{aligned} &\frac{1}{2} \\ &|(0,1)| = | \mathbb{R} | \\ &f:(0,1) \longrightarrow \mathbb{R} \\ &x \longmapsto \frac{x^{\frac{-1}{2}}}{x(x-1)} \end{aligned} \] \[ \begin{aligned} 16 &= 2^4 f(16) = \frac{1}{4} = 4 \\ &= 2^{(4)} (1) \\ &= 2^{(4)} (2(1)-1) \\ 12 &= 2^{(3)} (2(1)-1) f(12) = \frac{2}{1}=1 \\ 20 &= 2^{2} (2(3)-1) f(20) = \frac{2}{3} \end{aligned} \] \[ \begin{aligned} q &= [0, a] \cap \mathbb{Q}\\ q &= \frac{a}{b}\\ a &\in \omega\\ b &\in \mathbb{N}\\ 2^q(2b-1) \end{aligned} \]Now, consider the function:

\[ f : (0, 1) \longrightarrow \mathbb{R} \text{ defined by } x \longmapsto \frac{x^{-\frac{1}{2}}}{\sqrt{x(1-x)}} \text{ for all } x \in (0, 1). \]From the graph of \(f\), we see that \(f\) does “pass” the HLT, so \(f\) is 1-1. We also see that the range/image of \(f\) is in fact all of \(\mathbb{R}\), so \(f\) is onto.

This means we will have \(f\) is a bijection, so that:

\[ |(0, 1)| = |\mathbb{R}| \]Previously, we saw that:

\[ |\mathbb{N}| = |(0, \infty) \cap \mathbb{Q}| = \aleph_0 \]We will consider a (new) function \(F: \mathbb{N} \longrightarrow [0, \infty) \cap \mathbb{Q}\) defined by:

\[ 2^a (2b - 1) \longmapsto \frac{a}{b} \]Factor out all powers of 2. Remaining odd part.

Examples:

\[ \begin{aligned} 1 &= 2^0 (2 \cdot 1 - 1) \longmapsto \frac{0}{1} = 0 \\ 2 &= 2^1 (2 \cdot 1 - 1) \longmapsto \frac{1}{1} = 1 \\ 3 &= 2^0 (2 \cdot 2 - 1) \longmapsto \frac{0}{2} = 0 \\ 4 &= 2^2 (2 \cdot 1 - 1) \longmapsto \frac{2}{1} = 2 \\ 20 &= 2^2 (2 \cdot 3 - 1) \longmapsto \frac{2}{3} \\ 60 &= 2^2 (2 \cdot 8 - 1) \longmapsto \frac{2}{8} = \frac{1}{4} \end{aligned} \]It is clear that this function is not 1-1 (We already have \(f(1)=f(3)=0\)).

It is also easy to see that this function is onto:

Choose any non-negative rational number, \(q\).

As \(q\) is non-negative and rational, we can write \(q\) in the form \(q = \frac{a}{b}\)

where \(a \in \mathbb{W}\) and \(b \in \mathbb{N}\).

Notice that:

\(2^{a}(2b-1)\) will be natural (this takes a little work to verify).

- When \(a \in \mathbb{W}\), \(2^{a}\) will be natural (\(2^{0} = 1 \in \mathbb{N}\), and for \(a>1\), \(2^a\) is natural by the closure of \(\mathbb{N}\) under multiplication, and for \(a=1\), \(2^1 = 2 \in \mathbb{N}\).)

- As \(b \in \mathbb{N}\), \(2b-1\) is an integer (closure of \(\mathbb{Z}\) under multiplication and subtraction). Also, \(b \geq 1\), so \(2b \geq 2\), and \(2b - 1 \geq 1\). As \(2b - 1 \geq 1\) and \(2b - 1 \in \mathbb{Z}\), we have that \(2b-1 \in \mathbb{N}\).

- As \(2^a \in \mathbb{N}\) and \((2b-1) \in \mathbb{N}\), by closure of \(\mathbb{N}\) under multiplication, \(2^a(2b-1) \in \mathbb{N}\), so \(2^a(2b-1)\) is in the domain of \(f\).

Then, we have: \(f(2^{a}(2b-1)) = \frac{a}{b} = q\). As \(q \in [0, \infty) \cap \mathbb{Q}\) was arbitrary, \(f\) is a surjection.

We now have \(f: \mathbb{N} \xrightarrow{onto} [0, \infty) \cap \mathbb{Q} (2^a(2b-1) \mapsto \frac{a}{b})\)

We can use this function to “build”/define a bijection \(g: \mathbb{N} \xrightarrow{onto} [0, \infty) \cap \mathbb{Q}\)

To do this, we use the same “skipping” idea that we used previously.

\(f(1) = 0 = g(1)\)

\(f(2) = 1 = g(2)\)

\(f(3) = 0 \text{ (skip)}\)

\(f(4) = 2 = g(3)\)

\(f(5) = 0 \text{ (skip)}\)

\(f(6) = \frac{1}{2} = g(4)\)

\(f(7) = 0 \text{ (skip)}\)

\(f(8) = 3 = g(5)\)

\(f(9) = 0 \text{ (skip)}\)

\(f(10) = \frac{1}{3} = g(6)\)

\(f(11) = 0 \text{ (skip)}\)

\(f(12) = 1 \text{ (skip)}\)

\(f(13) = 0 \text{ (skip)}\)

\(f(14) = \frac{1}{2} \text{ (skip)}\)

\(f(15) = 0 \text{ (skip)}\)

\(f(16) = 4 = g(7)\)

\(f(17) = 0 \text{ (skip)}\)

\(f(18) = \frac{1}{5} = g(8)\)

\(f(19) = 0 \text{ (skip)}\)

\(f(20) = \frac{2}{3} = g(9)\)

\(f(21) = 0 \text{ (skip)}\)

\(f(22) = \frac{1}{6} = g(10)\)

\(f(23) = 0 \text{ (skip)}\)

\(f(24) = \frac{3}{2} = g(11)\)

\(f(25) = 0 \text{ (skip)}\)

\(f(26) = \frac{1}{7} = g(12)\)

\(f(27) = 0 \text{ (skip)}\)

Again, by only skipping repeats, we still will be onto, but we now will pass the “HLT” and we have a 1-1 function.

This tells us that we have:

\(| \mathbb{N} | = | [0, \infty) \cap \mathbb{Q} | = \aleph_0\)

\[ \begin{aligned} & f: \mathbb{R} \text{ onto } \mathbb{N} \\ & x \mapsto \lfloor|x|\rfloor + 1 \\ & 0 \mapsto 1 \\ & \pi \mapsto 4 \\ & 4.3 \mapsto 5 \\ & 1 \mapsto 2 \end{aligned} \] \[ \begin{aligned} f(1) \\ f(.1) \\ f(2) \end{aligned} \]Can you find \(f:(0,1] \xrightarrow[\text{Onto}]{1-1} (0,1)\) to show that \(|(0,1]| = |(0,1)|\) ?

\[ f: \omega \xrightarrow[\text{Onto}]{1-1} \mathbb{N}, n \mapsto n+1 \] \[ |\omega| = |\mathbb{N}| = \aleph_0 \] \[ \begin{aligned} 0 &\mapsto 1 \\ 1 &\mapsto 2 \\ 2 &\mapsto 3 \\ \vdots \end{aligned} \]Notation Detour: Consider a (partial) function (f: A \rightarrow B) (i.e., (f \subseteq A \times B) and (f) satisfies the VLT.)

Input Domain of (f = A)

Domain of (f = {x \in A ,|, (\exists y \in B)((x, y) \in f)} = \text{Dom}(f)) *

(f) is a total function when (\text{Dom}(f) = A) (and we write (f: A \rightarrow B))

Codomain of (f = B = \text{Cod}(f))

Range/Image of (f = {y \in B ,|, (\exists x \in A)((x, y) \in f)} = \text{Range}(f) = \text{Im}(f)) *

Graph of (f) is the set of all ordered pairs in the function (often denoted just by (f))

- In the definition of (\text{Dom}(f)) and (\text{Range}(f)), we are referring to the graph of (f).

Technicality: Two functions may have the same graph, but not be the same,

i.e., exactly the same ordered pairs but either the input domains differ, or the codomains differ (or both differ).

Examples:

- (f_1: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}) with (x \mapsto \sqrt{x})

- (f_2: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow [0, \infty)) with (x \mapsto \sqrt{x})

- (f_3: [0, \infty) \rightarrow \mathbb{R}) with (x \mapsto \sqrt{x})

- (f_4: [0, \infty) \rightarrow [0, \infty)) with (x \mapsto \sqrt{x})

(f_1, f_2, f_3) and (f_4) all have the same graph, but are different functions.

Domain Restrictions: Consider a (partial) function \(f: A \rightarrow B\) and a set \(C\).\

We can “create” a new function \(f|_C\) by “restricting the domain of \(f\) to \(C\).\

\(f|_C: (A \cap C) \rightarrow B\) (New Input Domain)\

The graph of \(f|_C\) is given by:\

\(f|_C = {(x,y) \in f \ | \ x \in C }\)\

(We make the domain smaller to only include values in \(C\))

Example: Consider \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(x \mapsto x^2\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

**Note:** \\(C\\) need not be a subset of \\(A\\). If \\(C\\) has "extra" values/values not in \\(A\\), they are ignored.

Eg., let \\(g : \omega \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}\\) defined by \\(n \mapsto (-1)^n \cdot n^2\\) for all \\(n \in \omega\\).\\ \\(g = \{(0,0), (1,-1), (2,4), (3,-9), (4,16), (5,-25), ... \}\\)

\\(g|_{\mathbb{N}} = \{(1,-1), (2,4), (3,-9), (4,16), (5,-25), ... \}\\)

\\(g|_{\{-5,-3,0,1,2\}} = \{(0,0), (1,-1), (2,4)\}\\)

\\(g|_{\{...,-50, -40, -30, -20, -10\}} = \emptyset\\)

Set Images: Consider a (partial) function \(f: A \rightarrow B\) and a set \(C\).

The image of \(C\) under \(f\) is defined to be the set of all “output” values when elements from \(C\) are “inputted” into \(f\):

\[ \{ y \in B \mid (\exists x \in C) ((x,y) \in f) \} \]This is just \(\text{Im}(f|_C)\).

Notation: The image of \(C\) under \(f\) is denoted by: \(f’‘C\)

\[ f''C = \text{Im}(f \cap C) = \{ y \in B \mid (\exists x \in C) ((x,y) \in f) \} \]Example: Consider \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(x \mapsto x^2\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

\[ \begin{aligned} f''\{0, 2, 4, 6\} &= \{ f(0), f(2), f(4), f(6) \} = \{0, 4, 16, 36\} \\ f''\{-2, -1, 0, 1, 2\} &= \{ f(-2), f(-1), f(0), f(1), f(2) \} = \{0, 1, 4\} \\ f''(1, 5] &= \text{Im}(f \cap (1, 5]) = (1, 25] \\ f''(-2, 3) &= \text{Im}(f \cap (-2, 3)) = [0, 9) \\ f''(-3, -1] &= \text{Im}(f \cap (-3, -1]) = [1, 9) \\ f''\{ i+i, 1-i \} &= \emptyset \\ f'' \emptyset &= \emptyset \end{aligned} \]The image of a set is always defined; \(f(i)\) is undefined here, so \(f’’{i} = \emptyset\).

f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}, x \mapsto x^2

\text{Graph of } f = { (2,4), (3,9), (-1, 1), (\pi, \pi^2), (\sqrt{2}, 2), \dots }

\[ \begin{aligned} g|_{[-4,5]} &= \{(0,0), (1,-1), (2,4), (3,-9), (4,16), (5,-25)\} \\ g|_{(2,3)} &= \emptyset \\ g|_{(2,4)} &= \{(3,-9)\} \end{aligned} \] \[ \begin{aligned} f\{ -2,-1,0,1,2 \} &= \{ (-2,4), (-1,1), (0,0), (1,1), (2,4) \} \\ \text{Dom}(f\{-2,-1,0,1,2\}) &= \{ -2,-1,0,1,2 \} \\ f\text{``Imagem"} (f\{-2,-1,0,1,2\}) &= \{0,1,4 \} \end{aligned} \]F’’(-3,-1)

\(g: { \emptyset, { \emptyset } } \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\)

\(g(\emptyset) = 17\)

\(g({ \emptyset }) = 11\)

\(g = \emptyset\)

\(g({ \emptyset } = { 17 }”\)

\(g(\emptyset) \neq g(" \emptyset)\)

\(g({ \emptyset }) \neq g( " { \emptyset } “)\)

Consider \(f: A \to B\) and a set \(C\). We denote the image of \(C\) under \(f\) by either \(\text{Im}(f(C))\) or \(f’‘C\). Sometimes people write \(f(C)\). This notation can be problematic.

Consider a function whose input domain consists of sets which is defined by:

\(A \mapsto A \cup {A}\). (\(S(A) = A \cup {A}\))

Now: \(S(\emptyset) = \emptyset \cup {\emptyset} = {\emptyset}\) \(S({\emptyset}) = {\emptyset} \cup {{\emptyset}} = {\emptyset, {\emptyset}}\) \(S({\emptyset, {\emptyset}}) = {\emptyset, {\emptyset}} \cup {{\emptyset, {\emptyset}}} = {\emptyset, {\emptyset}, {\emptyset, {\emptyset}}}\)

\(S’’\emptyset = \emptyset\) \(S’’{\emptyset} = {S(\emptyset)} = {{\emptyset}}\) \(S’’{\emptyset, {\emptyset}} = {S(\emptyset), S({\emptyset})} = {{\emptyset}, {\emptyset, {\emptyset}}}\)

Notice: \(S(\emptyset) \neq S’’\emptyset\) \(S({\emptyset}) \neq S’’{\emptyset}\) \(S({\emptyset, {\emptyset}}) \neq S’’{\emptyset, {\emptyset}}\)

``\(f’‘C\) is defined for every set \(C\) (if \(C\) is not a set, undefined)

\(f(C)\) is defined for every \(C \in \text{Dom}(f)\) (if \(C \notin \text{Dom}(f)\), undefined)

Concerning Domain Restrictions & Changing Codomains

If \(f: A \rightarrow B\) is a partial function, \(f|_{\text{dom}(f)}: \text{dom}(f) \rightarrow B\) is a total function.

If \(f: A \rightarrow B\) is a function, we can find some set \(\hat{A} \subseteq A\) such that

\(f|_{\hat{A}} : \hat{A} \rightarrow B\) is an injection.

E.g. \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\), defined by \(x \mapsto x^2\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

\(f|_{[0, \infty)}: [0, \infty) \mapsto \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(x \mapsto x^2\) for all \(x \in [0, \infty)\) is an injection.

If \(f: A \rightarrow B\) is a function, we can change the codomain to create a new function

\(f: A \xrightarrow{\text{onto}} \text{Im}(f)\) that is a surjection.

E.g. \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\), defined by \(x \mapsto x^2\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\)

\(f: \mathbb{R} \xrightarrow{\text{onto}} [0, \infty)\), defined by \(x \mapsto x^2\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) is a surjection.

Comment: Let \(f: A \rightarrow B\) be a function. Range\((f) = \text{Image}(f) = f’‘A\).

(If \(f: A \rightarrow B\), Range\((f) = \text{Im}(f) = f’‘A = f’’\text{dom}(f)\).)

\[ \begin{aligned} f: \mathbb{R} &\longrightarrow \mathbb{R}, x \longmapsto x^2 \\ f^{-1}(\{1, 4, 9\}) &= \{-3, -2, 1, 2, 3\} \\ f^{-1}(\{-6, -1, 0, 1, 36\}) &= \{0, 1, 6\} \\ f^{-1}(\{-\sqrt{3}, -\sqrt{2}, -1, 0, 1, \sqrt{2}, \sqrt{3}\}) &= \{-2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3\} \\ f^{-1}(\emptyset) &= \{-5, -3\} = \emptyset \\ \text{undef.} \\ f(\emptyset) &= \emptyset \end{aligned} \](-2,-1] \cup [1,2)

[-\sqrt{3},\sqrt{3}]

Inverse Set Images \ Let \(f: A \to B\), and let \(C\) be a set. \ The inverse image of \(C\) under \(f\) is denoted by \(f^{-1}(C)\) and is defined by:

\[ f^{-1}(C) = \{x \in A \mid (\exists y \in C) ((x, y) \in f)\} \]``Idea”: \(f^{-1}(C)\) is the set of all values in the domain of \(f\) that map to something in \(C\).

``Notes": \(f^{-1}(C)\) is defined for every set \(C\) (only undefined if \(C\) is not a set)

\(f^{-1}(B) = f^{-1}(\text{Range}(f)) = \text{Dom}(f)\)

Example: Consider \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) defined by \(x \mapsto x^2\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

\[ \begin{aligned} f^{-1}(\{4, 5\}) &= \{-\sqrt{5}, -2, 2, \sqrt{5}\} \\ f^{-1}(\{-1, 0, 2\}) &= \{-\sqrt{2}, 0, \sqrt{2}\} \\ f^{-1}(\{-4, -5, -6\}) &= \emptyset \\ f^{-1}([-2, 3]) &= [-\sqrt{3}, \sqrt{3}] \\ f^{-1}([-4, -2]) &= \emptyset \\ f^{-1}([1, 4)) &= (-2, -1] \cup [1, 2) \\ f^{-1}((0, 7]) &= [-\sqrt{7}, 0) \cup (0, \sqrt{7}] \end{aligned} \] \[ \begin{aligned} x &= 0.\overline{9} \\ 10x &= 9.\overline{9} \\ x &= 0.\overline{9} \\ \hline 9x &= 9 \\ x &= \frac{9}{9} = 1 \end{aligned} \]